![An exceptionally anhua-decorated tianbai-glazed meiping, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424)]()

![1]()

![2]()

![44a0529e2bfafb0370a1061ab557f2b2]()

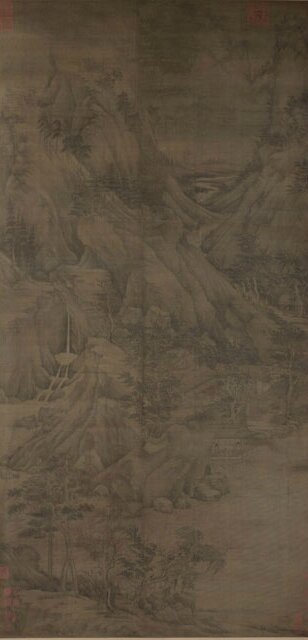

Lot 3. An exceptionally anhua-decorated tianbai-glazed meiping, Ming dynasty, Yongle period (1403-1424). Estimate 2,300,000 — 2,800,000 USD. Photo: Sotheby's

evenly potted of generous proportions with the full rounded shoulders rising at a gently flared angle from the base and sweeping to a short waisted neck, finely incised around the body with a broad frieze of leafy peony scrolls bearing four large, full blossoms, with smaller subsidiary buds, framed below by a band of classic scroll at the foot, and a ruyi-lappet collar filled with lotus sprays at the shoulder, all within double-line borders, covered overall with a fine and smooth 'sweet white' (tianbai) glaze, continuing over the mouth rim, the base left unglazed to reveal the fine white body. Height 12 5/8 in., 32.2 cm

Provenance: Christie's New York, 17th September 2008, lot 245.

Immaculate like piled-up snow

Regina Krahl

White porcelain was of special significance for the court during the Yongle reign (1403-24) and this vessel represents one of the classic styles commissioned from the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen. The present piece is remarkable for its particularly fine potting and its smooth and tactile glaze and illustrates the phenomenal advances made by Jingdezhen’s potters, since porcelains began to be made there officially in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

Monochrome white wares were so important in the Yongle period that a special glaze of smooth, creamy appearance was developed to create a distinctive monochrome white style as against porcelain that had been left undecorated. What has become known as tianbai, ‘sweet white’, is a glaze that has shed the bluish tinge of the earlier Jingdezhen qingbai (‘bluish-white’) wares, is less opaque than the earlier shufu wares, and has a richer, more luscious presence than contemporary glazes used over underglaze-blue designs, which were primarily meant to be invisible so as not to obscure the blue decoration. The pure white porcelain, which is not unlike porcelains we are using today, resulted from the combination of a kaolin-rich paste with very low iron and titanium content and a glaze containing mainly glaze stone and no glaze ash.

The term tianbai was apparently coined by Huang Yizheng, a writer of the Wanli period (1573-1620) in his Shiwu ganzhu (‘Purple Pearl [memory bead] for Remembering Things’) of 1591, which discusses a range of topics including different types of tea. In this book he characterizes the glaze, which he thought was common both in the Yongle and Xuande (1426-1435) periods, as “white like congealed fat, immaculate like piled-up snow” (Imperial Porcelain of the Yongle and Xuande Periods Excavated from the Site of the Ming Imperial Factory at Jingdezhen, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1989, p. 35; and Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan, ed., Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan guancang wenwu yanjiu congshu/Studies on the Collections of the National Museum of China. Ciqi juan: Mingdai [Porcelain section: Ming dynasty], Shanghai, 2007, p. 13).

Although the majority of Yongle finds at the Ming imperial kiln site in Jingdezhen are apparently ‘sweet white’ wares (in two consecutive Yongle strata at the eastern section of Zhushan Zhonglu in Jingdezhen city over 98%), preserved specimens are much rarer than contemporary blue-and-white porcelains, which can only reflect the immense difficulty to create specimens, where the glaze turned out satisfactorily and which therefore were delivered rather than being destroyed and interred near the kilns (see Hong Kong 1989, op.cit., p. 19).

The importance of white wares is certainly due in part to their relevance in Tibetan Buddhist rituals, which the Yongle Emperor passionately patronized and which is reflected in Buddhist shapes such as ‘monk’s cap’ ewers and stem bowls, as well as probably tens of thousands of porcelain bricks ordered for the Porcelain Pagoda in Nanjing, of which over 2000 have been unearthed at the kiln sites. The imperial commissioning of white wares, however, extended well beyond pieces used in a Buddhist context. Besides foreign shapes, particularly copied after metal wares from the Islamic lands of the Middle East, and shapes whose source and usage are still not properly understood, there are wares of purely Chinese character such as the yuhuchunping or the meiping. Meiping vases, or jars, since in the Yongle period they were probably still used as wine containers rather than flower vases, were made in various sizes and despite – or perhaps exactly because of – their quintessentially Chinese flair were not only popular in China, but also abroad. Fine Yongle examples are preserved in the Chinese palace collections in Beijing and Taipei as well as in the Safavid and Ottoman royal collections in Iran and Turkey, but otherwise are very rare.

It seems that the exact outline of the meiping shape was much experimented with at Jingdezhen. It had already been altered from the Yuan (1279-1368) to the Hongwu period (1368-1398); two new versions of Yongle and of Xuande date are known from rejects at the kilns, another appears to be preserved in a single example in the Shanghai Museum. Given the superb silhouette of the piece offered here, it is not surprising that this present version triumphed and was most frequently used in both periods not only for white but also for blue-and-white specimens.

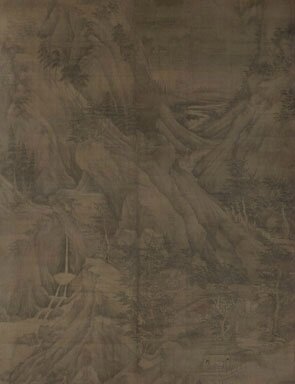

Compare an undecorated example of more heavy, less elegant proportions, with a thick rim flange, the only ‘sweet-white’ Yongle meiping published from the Ming imperial kiln site excavations, in Jingdezhen chutu Ming chu guanyao ciqi/Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain Excavated at Jingdezhen, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1996, cat. no. 101 (fig. 1); with a larger, plain ‘sweet-white’ meiping of quite different proportions in the Shanghai Museum, also attributed to the Yongle reign, in Lu Minghua, Shanghai Bowuguan zangpin yanjiu daxi/Studies of the Shanghai Museum Collections : A Series of Monographs. Mingdai guanyao ciqi [Ming imperial porcelain], Shanghai, 2007, pl. 3-18 (fig. 2); and an undecorated meiping, excavated with cover and stand from the Xuande stratum of the Ming imperial kiln sites, which is closer again to Yuan prototypes, illustrated in Mingdai Xuande yuyao ciqi/Imperial Porcelains from the Reign of Xuande in the Ming Dynasty, Beijing, 2015, pl. 63. A smaller lotus-decorated Yongle meiping, similar to the present piece in shape, is compared with a Yuan dynasty piece, both in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in Oriental Ceramics. The World’s Great Collections, vol. 10, Tokyo, New York and San Francisco, 1980, col. pls 46 and 47.

![A tianbai-glazed meiping, Yongle period (1403-1424)]()

fig. 1. A tianbai-glazed meiping, Yongle period (1403-1424), Ming imperial kiln site excavations.

![A tianbai-glazed meiping, Yongle reign (1403-1424), Shanghai Museum]()

fig. 2. A tianbai-glazed meiping, Yongle reign (1403-1424), Shanghai Museum

Meiping such as the present one are known with various subtle, incised designs, most of which are also known from contemporary versions painted in underglaze cobalt blue. The lush peony pattern of the present piece, with small lotus sprays in a cloud collar around the shoulder and a florid classic scroll at the base, is extremely rare. White jars of this shape are better known with a variety of lotus designs, generally of smaller size. Compare a piece in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Minji meihin zuroku [Illustrated catalogue of important Ming porcelains], vol. 1, Tokyo, 1977, pl. 25, together with the blue-and-white counterpart, pl. 11; another in the Palace Museum, Beijing, published in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Monochrome Porcelain, Hong Kong, 1999, pl. 99; one in the National Museum of China, Beijing, is illustrated in Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan guancang wenwu yanjiu congshu/Studies on the Collections of the National Museum of China. Ciqi juan: Mingdai [Porcelain section: Ming dynasty], Shanghai, 2007, pl. 25, with a blue-and-white version, pl. 10.

Four such meiping with lotus design were preserved in the Ardabil Shrine in Iran, see John Alexander Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine, Washington, D.C., 1956 (rev. ed. London, 1981), cat. nos 29.719-722, one of them illustrated pl. 115, together with its blue-and-white counterpart, pl. 51; and one in Topkapi Saray in Turkey, see Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, ed. John Ayers, London, 1986, vol. 2, cat. no. 636, with a related blue-and-white design, cat. no. 623.

Yongle ‘sweet-white’ meiping with lotus designs were sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 5th November 1997, lot 1368; and in our London rooms, 17th December 1996, lot 71; and 13th November 2002, lot 104, the latter again at Christie’s Hong Kong, 29thMay 2007, lot 1481; a larger one of slightly different proportions was sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 31st October 1994, lot 561.

Sotheby's. Ming: The Intervention of Imperial Taste, New York, 14 mars 2017, 10:00 AM