![2]()

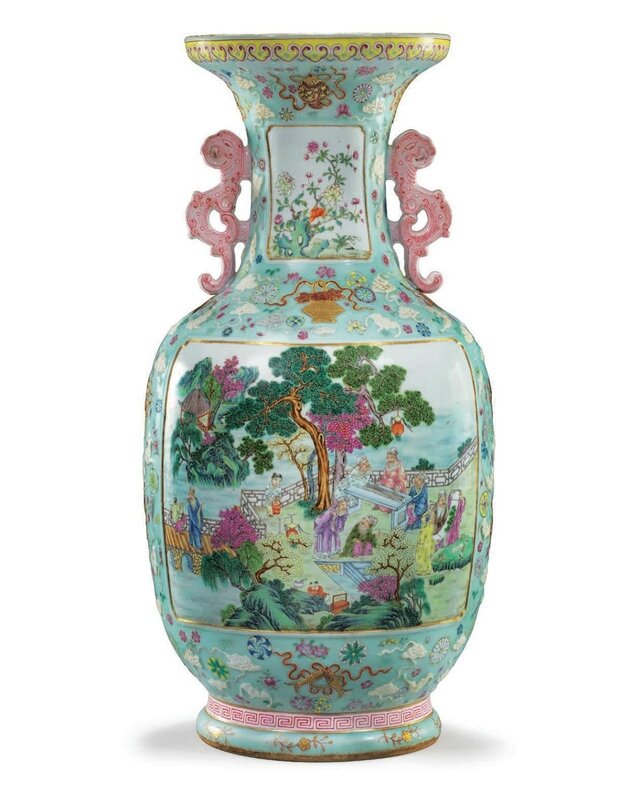

Portrait of King Jeongjo (1776-1800). Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

CLEVELAND - Chaekgeori: Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens showcases a unique type of Korean still-life painting called chaekgeori (pronounced check-oh-ree), translated as “books and things.” They commonly feature scholarly objects, exotic luxuries, symbolic flowers, and gourmet delicacies.

The exhibition showcases 9 unique type of Korean still-life painting. Chaekgeori 책거리 (pronounced check-oh-ree), literally translated as “books and things,” are painted screens that depict scholarly objects, exotic luxuries, symbolic flowers, and gourmet delicacies dispersed in artful arrangements on bookshelves.

The Chaekgeori art and the King Jeongjo

Such screens were praised by King Jeongjo (reigned 1776–1800), and were enthusiastically collected by the educated elite throughout the 19th and early 20th century in Korea. By the late 1800s, chaekgeori screens embellished the studies of scholars and aristocrats as well as the homes of middle-class merchants.

The exhibition features nine large-scale screens ranging from the 19th through the 21st centuries on loan from the Korean Folk Village, Yongin, Korea and the Sungok Memorial Hall, Monkpo, Korea as well as from private collections. The exhibition catalogue reveals new scholarship about the artist who painted the rare, 10-panel folding screen, Books and Scholars’ Accouterments, acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2011.

The primary motif of chaekgeori is books, the objects Korean intellectuals traditionally associated with knowledge and social distinction. Preferred by the court and elite classes, chaekgado, translated as “picture of bookshelves,” is a subgenre of chaekgeori developed in the second half of the 18th century that represents a Korean collectors’ desire to amass books on diverse topics to express their aesthetic discernment.

This desire for books and other commodities, including writing implements, exotic foreign luxuries, symbolic flowers and gourmet delicacies, set in motion a significant social and cultural shift toward a fascination with material culture that continues in Korea today and finds its expression in the exhibition’s contemporary works. Chaekgeori: Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens allows viewers to witness the period when Koreans became active participants in global consumerism through these passionate collecting activities.

Exhibition Highlights

![1-1]()

Books and Scholars’ Accouterments (chaekgeori), late 1800s. Yi Taek-gyun (Korean, 1808–after 1883). Ten-panel folding screen, ink and color on silk; each panel: 197.5 x 39.5 cm. Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund, 2011.37. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![1]()

Books and Scholars’ Accouterments (chaekgeori) (detail), late 1800s. Yi Taek-gyun (Korean, 1808–after 1883). Ten-panel folding screen, ink and color on silk; each panel: 197.5 x 39.5 cm. Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund, 2011.37. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![3]()

Chaekgeori, late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 119 x 51 cm. Korean Folk Village, Yongin. Courtesy of the Korean Folk Village, Yongin.

![3-1]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 119 x 51 cm. Korean Folk Village, Yongin. Courtesy of the Korean Folk Village, Yongin.

![4]()

Chaekgeori, late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, embroidery on silk; each panel: 166 x 38.5 cm. Korean Folk Village, Yongin. Courtesy of the Korean Folk Village, Yongin.

![4-1]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, embroidery on silk; each panel: 166 x 38.5 cm. Korean Folk Village, Yongin. Courtesy of the Korean Folk Village, Yongin.

![4-2]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, embroidery on silk; each panel: 166 x 38.5 cm. Korean Folk Village, Yongin. Courtesy of the Korean Folk Village, Yongin.

![5]()

Chaekgeori, early 1900s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 105 x 46.5 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![5-1]()

Chaekgeori (detail), early 1900s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 105 x 46.5 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![5-2]()

Chaekgeori (detail), early 1900s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 105 x 46.5 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![5-3]()

Chaekgeori (detail), early 1900s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 105 x 46.5 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![5-4]()

Chaekgeori (detail), early 1900s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 105 x 46.5 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![6]()

Chaekgeori, late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 55.7 x 31.7 cm. Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea. Courtesy of Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul.

![6-1]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 55.7 x 31.7 cm. Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea. Courtesy of Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul.

![6-2]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 55.7 x 31.7 cm. Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea. Courtesy of Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul.

![6-3]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 55.7 x 31.7 cm. Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea. Courtesy of Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul.

![6-4]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Eight-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 55.7 x 31.7 cm. Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea. Courtesy of Songok Memorial Hall, Seoul.

![7]()

Chaekgeori, late 1800s. Anonymous. Six-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 67 x 33 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![7-1]()

Chaekgeori (detail),

![7-2]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Six-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 67 x 33 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

![7-3]()

Chaekgeori (detail), late 1800s. Anonymous. Six-panel folding screen, ink and color on paper; each panel: 67 x 33 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

A very important discovery made in the Museum: the artist Seal

William Griswold, Director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, said, “Since many of the screens presented in the exhibition are being shown and studied for the first time, this exhibition has added significant research to the field of East Asian art. We are also thrilled to announce that through collaborative research between Dr. Sooa McCormick of the Cleveland Museum of Art and Prof. Byungmo Chung of Gyeongju University, along with support from the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation, the Cleveland museum’s chaekgeori screen is determined to be the work of the famous Korean court painter Yi Taek-gyun from the 19th century. This recent discovery demonstrates how cultural collaborations between institutions and scholars are essential for the advancement of knowledge.” “Chaekgeori maintained its popularity in Korea for more than two centuries, and we are thrilled to introduce our visitors to this distinctive genre of still-life painting.”

Functioning the same as a signature in Western culture, in chaekgeori, a seal impression is often included to reveal the painter’s identity. Due to its discreet manner, a seal impression is called a “hidden” seal. Only about 12 works that bear the painter’s “hidden” seal are known today. This CMA screen has one on the third panel (from the right), which was recently examined by Dr. Sooa McCormick and Prof. Byungmo Chung, along with support from the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation. Through the recent discovery of this “hidden” seal, the museum learned the screen is one of only three known existing works by Yi Taek-gyun, a prominent royal court painter active in the second half of the 19th century.

Freed from the confinement of bookshelves, various objects are scattered throughout the picture plane as if floating in the air. While this “floating” type became quite common by the end of the 19th century, chaekgeori done in embroidery remained rare. The particular embroidery work used in this screen was developed in Anju province in North Pyeongan Province, a place known for high-quality silk and skilled male embroiderers. In order to increase palpable texture, Anju embroiderers used thick twisted silk threads and applied an underlay of stitches before the final embroidery work was added.

Chaekgeori by contemporary artist

Kyoungtack Hong, born and based in Seoul, South Korea, Kyoungtack Hong is known for his photorealistic depictions of things that surround our contemporary lives. Like chaekgeori, Hong filled the surface of the work with “stuff,” ranging from books to Lego blocks and Barbie dolls that he has collected over the years. Hong’s room crammed with myriad things speaks to the intrinsic human desire to possess things, and at the same time the chaotic arrangement of randomly chosen objects indicates that “materialism” never entirely brings spiritual fulfillment.

![8]()

Library 3, 1995–2001. Kyoungtack Hong (Korean b. 1968). Oil on canvas; 181 x 226.1 cm.© Kyoungtack Hong.

![9]()

Library—Mt. Everest, 2014. Kyoungtack Hong (Korean b. 1968). Acrylic and oil on linen; 194 x 259 cm. © Kyoungtack Hong.

Sat, 08/05/2017 to Sun, 11/05/2017 - Julia and Larry Pollock Focus Gallery | Gallery 010