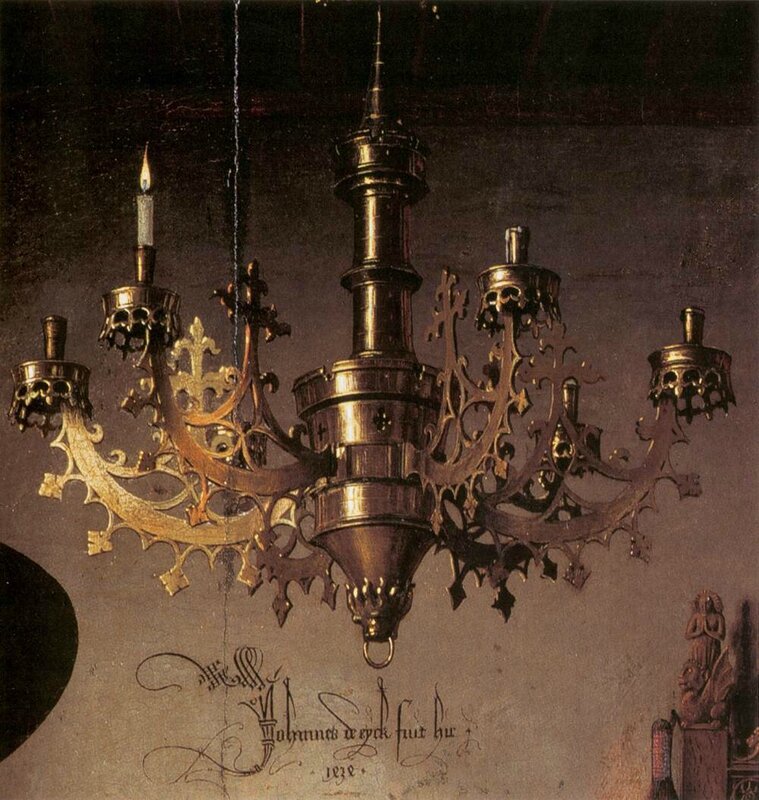

Kappelkrone (Tabernacle Chandelier), copper alloy, South Netherlandish or German, probably Dinand or Nuremberg, late 15th century. Estimate: £200,000-300,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

LONDON.- Sotheby’s London sale of Old Master Sculpture & Works of Art on 10 July 2014 will be led by a magnificent Gothic chandelier dating to the closing decades of the 15th century which finds a tantalisingly direct parallel in Jan van Eyck’s celebrated oil painting The Arnolfini Portrait in the National Gallery, London. Estimated at £200,000-300,000, and probably made in either Dinant, in the Southern Netherlands, or Nuremberg, in Southern Germany, two of the leading centres for metalwork production in Europe at the time, the chandelier is very rare. Few 15th-century examples of this scale survive, to be found only in leading museums and private collections.

At the centre of the tabernacle stands a small statuette of the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven; affixed to the tabernacle are two tiers of arms, fitted with candleholders and drip-pans. The scale of the whole ensemble is breath-taking, and would have created a dazzling effect once illuminated.

Impressive, multi-tiered, chandeliers were the preserve of the wealthiest private citizens, serving as signifiers of taste and prestige. The centrepiece of Van Eyck’s interior is a chandelier very similar in detail, with arms sprouting leaves, and a lion mask below the central architectural matrix. Chandeliers were often given as wedding gifts, and the example in the painting may, therefore, have been an expensive present to celebrate Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini’s marriage.

Details in the example being offered for sale suggest equally persuasive arguments for either a Dinant or Nuremberg origin. The relationship between the two centres was very close, most significantly as a result of the sacking of Dinant by Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, in 1466, forcing many of the town’s craftsmen to flee to cities including Nuremberg.

Kappelkrone (Tabernacle Chandelier), copper alloy South Netherlandish or German probably Dinand or Nuremberg, late 15th century. Estimate: £200,000-300,000. Photo: Sotheby's.

seven of the eight arms of the lower tier numbered 1 to 7using a ring and dot numeric system, the supporting slots affixed to the matrix numbered correspondingly

copper alloy, with a central iron rod and metal pins; 110 by 92cm., 43 1/4 by 36 1/4 in. overall.

Provenance: Private collection, Franconia, Germany, by 1982;

the present owner

Litterature: H. P. Lockner, 'Ein gotischer Tabernakelkronleuchter. Aufbau und Konstruktion',Kunst und Antiquitäten, Zeitschrift für Kunstfeunde, Sammler und Museen, 1982, no. 5. pp. 47-57

Notes: This magnificent Gothic chandelier dates to the closing decades of the 15th century. It was probably made in either Dinant, in the Southern Netherlands, or Nuremberg, in Southern Germany, two of the leading centres for metalwork production in Europe at the time. Impressive, multi-tiered, chandeliers were the preserve of the wealthiest private citizens, serving as signifiers of taste and prestige. Tantalisingly, the present chandelier finds a direct parallel in Jan van Eyck's celebrated oil painting The Arnolfini Portrait in the National Gallery, London (dated 1434; inv. no. NG186) (fig. 1). The centrepiece of Van Eyck's interior is a chandelier very like the present example, with arms sprouting leaves, and a lion mask below the matrix. Few 15th-century chandeliers of this scale survive, being found only in leading museums and a number of private collections. The present example is consequently very rare.

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife (detail), 1434. Inv. no. NG186. National Gallery, London © National Gallery, London.

The chandelier is composed around a central matrix of architectural form, following the design of a defensive tower or church spire. Running vertically through the centre of the matrix is an iron rod, which serves as the skeleton of the object. The rod terminates in an orb, around which the bottom of the matrix is constructed using rivets; these inner workings are concealed by the beautifully cast lion mask. As is outlined by Lockner, who provides a full analysis of the facture of the chandelier, this construction is typical of early chandeliers, fading out in the 16th century; it consequently affirms the 15th-century date of the object (Lockner, op. cit., pp. 47-48). The architectural structure or tabernacle, which is built up around the rod, is composed of multiple smaller components; in fact, according to Lockner, the entire chandelier is made up of some 92 individual elements (op. cit., p. 52). At the centre of the tabernacle stands a small statuette of the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven. The statuette is hollow, allowing the iron rod to pass through her. Affixed to the tabernacle are two tiers of arms, fitted with candleholders and drip-pans: a larger tier of 8 arms at the bottom and a smaller tier of 6 arms above. The chandelier is suspended from a hook connected to the finial at the top, which is adorned with an elaborate Gothic cross flower. As is to be expected with an object of this age and complexity, some of the elements are replaced, notably the candleholders without windows and the less ornate drip-pans. The scale of the whole ensemble is nevertheless breathtaking, and would create a dazzling effect once illuminated.

There is a near-identical chandelier of the same dimensions in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no. 1975.1.1422). This example comes from the Robert Lehman Collection and was acquired by Philip Lehman from Lord Duveen in 1917; it was bought by Duveen from a Frenchman named Maurice Chabrières-Arlès and had previously been in the collection of Jean-Baptiste Carrand (1792-1871). The chandelier is catalogued as Southern Netherlands, possibly Dinant, circa 1450-70. It seems likely that the Metropolitan chandelier was made by the same workshop. However, it should be noted that there are some differences. Unlike the present example, the candleholders are without windows and the drip-pans are reversed, recalling coronets. Thanks to Jan van Eyck's astonishing realism, we know that the drip-pans are the correct way round in the present chandelier, and the wrong way round in the Metropolitan example. However, these differences are easily explained, the drip-pans may have been reversed in the Metropolitan chandelier, and the candleholders simply replaced, as often happened. There is one final key difference. The present chandelier is distinguished by beautifully delicate arabesques applied to the lower finial using the punchwork technique. In contrast, the Metropolitan finial is undecorated. Nevertheless, the correspondences between the two chandeliers are otherwise very close, and even extend to the figure of the Virgin, which is cast from the same model.

Chandelier with tabernacle (Kapellenkrone), Southern Netherlands, ca. 1450–70. Inv. no. 1975.1.1422. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © 2000–2014 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Successful models were reproduced by workshops during the 15th-century. Another relevant example is the chandelier in the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. no. 2398-1855) which is thought to have been made in Germany between 1480 and 1520. This compares well with the present example in sporting a very similar lower finial, articulated with festoons running along the vertical skeletal borders. As in the present example, some of the candleholders have clearly been replaced, though, in this case, with spigots. Interestingly, however, the model is the same as another very fine chandelier in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no. 47.101.50a, b), which is on display in The Cloisters. The Museum has catalogued this example as South Netherlandish, possibly Dinant, late 15th century. It is surmounted with an angel, which is conceived in a very similar manner to the present Virgin, with analagous oblong eyes. The differences in cataloguing between the V&A and Metropolitan chandeliers, however, highlights the complexity of the history surrounding these important early objects, as well as the currently limited scholarship on them. It seems likely that all of the chandeliers mentioned originate from a single centre of production, as they all exhibit the same characteristic trefoil leaves branching out from the arms.

Brass chandelier, German or Flemish, 1480-1520, topped by an angel figure, with central rod and main body, 4 upper branches and 8 lower branches, lion mask lower finial. Inv. no. 2398-1855. Victoria and Albert Museum © V&A Images.

Chandeliers of this type appear in 15th-century Netherlandish art, most notably in The Arnolfini Portrait, but also in other paintings, such as Petrus Christus' Virgin and Child in an Interior in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City (inv. no. 65.51). What is interesting in regards to The Arnolfini Portrait is that, according to Lockner (op. cit.) chandeliers were often given as wedding gifts. The example in Van Eyck's picture may, therefore, be an expensive present to celebrate the union represented. As well as being employed to represent sumptuous or heavenly interiors, such chandeliers were frequently used for the glorification of God, and were placed in churches. In 1495, the German traveller Dr Jerome Munzer described over four hundred such chandeliers of differing sizes in Antwerp Cathedral; the sight must have been spectacular. Chandeliers such as the present example consequently had a clear association with the Low Countries and so it seems only natural that their centre of production would have been local. That the present chandelier could be Netherlandish is indicated by the presence of the characteristic leaves, which are also clearly present in Van Eyck's scene. Moreover, the statuette of the Virgin has notable similarities with late 15th-century Netherlandish figures; see, for example, the statuettes angels in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (inv. nos. N.M. 9545g and 9546g).

However, when the present chandelier was published by Lockner in 1982, he argued for a Nuremberg origin, citing the very thin and fine casting, which is consistent with Nuremberg work. Lockner also found a comparable for the elegant punchwork decoration on the lower finial in a choir lectern by Hans Wurzelbauer in the Mainkränkisches Museum, Würzburg, dating to 1644 (Lockner, op. cit., pp. 54-55). It is also the case that the characterful lion mask recalls the faces of lion aquamanilia made in Nuremberg, such as the example dating to circa 1400 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. no. 1994.244).

Dinant and Nuremberg were two of the foremost centres for metalwork in the 15th century. The town of Dinant, situated on the river Meuse in modern Belgium, was famed for its brass ware, termed dinanderie. Significantly, in 1466, many of the town's craftsmen were forced to flee to cities including Nuremberg, when it was sacked by Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Objects made in Nuremberg thenceforth in the Dinant style are likewise often referred to as dinanderie. The relationship between the two centres was consequently very close and it remains difficult to claim with certainty that a particular dinanderie object was made in one or the other city.

RELATED LITERATURE: E. Meyer, 'Der gotische Kronleuchter in Stans', Festschrift Hans R. Hahnloser, 1961, S. 152, pp. 151-184; O. ter Kuile,Koper & Bronz, cat. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1986, pp. 122-125, 150-151, nos. 170-172, 197-199; N. Netzer,Catalogue of Medieval Objects. Metalwork, cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston, 1991, pp. 128-129, no. 44; P. Barnet and P. Dandridge, Lions, Dragons, and other Beasts. Aquamanilia of the Middle Ages, Vessels for Church and Table, exh. cat. Bard Graduate Center, New Haven and London, 2006, pp. 142-143, no. 20

The present chandelier is accompanied by an energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence analysis (EDXRFA) report completed by Prof. Dr. Ernst-Ludwig Richter on 15 August 2009 stating that 'the results of samples 1-6 [from the chandelier] are entirely consistent with a late medieval origin of these parts of the chandelier'. It adds that the presence of certain replacements, which are consistent with a 19th or 20th century origin, 'support its authenticity'.

This analysis was confirmed by Dr Peter Northover of the University of Oxford, who examined the chandelier and the alloys used on 1 May 2014 and is in the process of preparing a written metallurgy report on the object.

A rare medieval stained glass window dating to circa 1260 has re-emerged, hidden amongst a group of 19th and 19th century stained glass windows that were purchased as a job lot at an auction in the US, over a century after it was last accounted for. The panel, illustrating a rare apocryphal scene from the Genesis, in which Adam bathes Eve after the birth of Cain, is one of two original sections of a window from Tours Cathedral known to have survived. The glass in the window – which combines two demi-medallions – is in a remarkable state of preservation, with radiant colours and precise painting, indications of the high class of craftsmanship of the school of Tours.

In 1810, a group of medieval windows were acquired by the Tours cathedral chapter in order to restore the glass in the cathedrals ambulatory chapels, which had probably been heavily damaged in the Revolution. Most likely purchased from the nearby Abbey Church of Saint Julien, the window was removed sometime in the middle of the 19th century as part of a large restoration project and stored, as was customary, in a glazier’s workshop at the time. It is unclear what happened to the window afterwards, but it probably found its way into the US in the early 20th century.

The faces in the window are lively and beautifully delineated by quickly painted lines – such finesse and heightened movement were among the innovations made by the Tours School. The somewhat worried countenances of the figures are also characteristic of glaziers from the West of France. An enormous amount of glass was installed in Tours cathedral between 1245 and 1267, creating a need for a glaziers workshop that developed a distinctive style. The window is estimated to bring £60,000-70,000.

Window with the Bath of Eve, West French, Tours, circa 1260. Leaded stained glass, in a later wood frame; window: 72.5 by 62.5cm., 28½ by 24½in.; frame: 79.5 by 69cm., 31¼ by 27 1/8 in. Estimate: £60,000-70,000. Photo: Sotheby's

Provenance: probably Abbey Church of Saint Julien, Tours;

part of the windows purchased by Tours Cathedral chapter, 1810;

probably central ambulatory chapel, Tours cathedral, until circa 1845-1863;

Leopold Lobin, Tours, circa 1845-1863 until early 20th century;

possibly Mr Champignol or Acézat, Paris;

possibly with Arnold Seligmann, Rey and Co, circa 1935;

private collection, USA

Notes: The present panel is the second original section of a window from Tours Cathedral to reemerge since it was last alluded to in New York in 1935. The glass is in a remarkable state of preservation and the radiant colours and precise painting illustrate the high class of craftsmanship of the school of Tours. The window combines two demi-medallions that illustrate a rare apocryphal scene from the Genesis, in which Adam bathes Eve after the birth of Cain.

In 1810, a group of medieval windows were acquired by the Tours cathedral chapter in order to restore the glass in the cathedral’s ambulatory chapels, which had probably been heavily damaged in the Revolution. The description of the windows made by Baron de Guilhermy some years later includes a window with the Life of Saint Julien. Since the saint is otherwise unrelated to the cathedral, it has been suggested that the windows were purchased from the nearby Abbey Church of Saint Julien. Among the newly installed glass was a window representing the Genesis, the second window of this subject in the cathedral. Despite the new additions the windows remained in a poor state and therefore a large “archeological restoration” was carried out by Leopold Lobin between 1845 and 1863. Lobin relocated some of the Saint Julien glass and removed the Genesis window altogether and stored it; as was customary in glazier’s workshops at the time. It is unclear what happened with the original window afterwards but in 1935 Jean Seligmann offered four Genesis panels to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York which apparantly came from the Saint-Martin Church in Tours via the heirs of a Tours glazier and a Parisian agent. The Seligmann panels were rightly deemed forgeries by the curators and were finally sold some years later at auction. In 1983 the panels were rediscovered set in two windows in Pomfret School, Connecticut, and it was established that they were indeed of comparatively recent manufacture. (Papanicolaou, op.cit., fig. 1 and CV US, Checklist I, 35) Tantalisingly, however, the Pomfret window incorporates copies of the present demi-medallions and another, extremely similar window with the Birth of Cain in an American private collection, suggesting that the original windows did enter the United States, possibly through Seligmann. (see Papanicolaou, op.cit., fig. 2)

The setting of the figures against a monochrome boldly coloured background and the swift, graceful painting of the expression and drapery, as well as the pattern of squares painted with quatrefoils are derived from Parisian models such as the programme in the Sainte-Chappelle. 12th and 13th century glass was coloured by adding metal oxides to its molten state. This so-called pot-metal glass only yielded a limited range of colours. The red glass is particularly recognisable since it had to be flashed against transparent glass in order to be thin enough to be translucent. The brown paint was applied afterwards and fired. Here it is done in the comparatively loose style of the mid-13th century: earlier painting generally still displays the geometric play of lines of the Romanesque era whilst after 1300 silver staining enables more refined tonality. The faces in the present window are lively and beautifully delineated by quickly painted lines. As such some of the details, like the eyebrows, eyes, and thumbs, have the appearance of sheet music. Such finesse and heightened movement are innovations for which the Tours School was responsible. The somewhat worried countenances of the figures are equally characteristic of glaziers from the West of France. Compare, for example, the flowing hair and single stroke with which the jawline of the figure in the bath was rendered with Eve from The Fall in the remaining Genesis window in the choir clerestory of the cathedral in Tours which dates to 1255-1260 (see Grodecki/ Brisac, op.cit., fig. 125). An enormous amount of glass was installed in Tours cathedral between 1245 and 1267, creating the need for a glaziers workshop that developed a distinctive style. That workshop would also have served local churches such as the Church of Saint Lucien, which was extensively remodelled between 1243 and 1259.

It is unclear which source the glaziers used for the Tours Genesis window. A Bathsheba that is remarkably similar to the present Eve, appears with an attendant holding a kettle in folio 41v of the mid-13th-century Morgan Crusader Bible (Pierpont Morgan Library, New York). Further illuminations feature the curtains suspended from a single knop. Figures heating water are also usually part of medieval bathing scenes. See for example Herr Jakob von Warte’s bath in the Codex Manesse from the early 14th century (Cod. Pal. germ. 848, f. 46v).

RELATED LITERATURE: L. Grodecki and C. Brisac, Gothic stained glass 1200-1300, London, 1985, p. 139, fig. 125; L. Morey Papanicolaou, “The other Tours Genesis windows”, Gesta XXXVII/2, 1998, pp.225-231; P. Williamson, Medieval and Renaissance stained glass in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2003, pp. 9-10

A limestone statue of Saint John the Baptist is one of only a handful of monumental stone carvings from the fabled workshops active in the Burgundian Netherlands in private hands. Attributed to Jan Crocq, who was active between 1486 and 1510 at the Bar and Lorraine court of Duke Rene II, the sculpture was probably carved in the first decade of the 16th century. Monumental in presence and measuring 163 cm in height, it was once part of an important altarpiece. The manner in which Crocq handles the stone is comparable to wood sculptures of the period. Crocq was the most important sculptor active in the court. A native of Flanders, he received regular payments from Rene II and his wife from 1499 to 1510, suggesting he was permanently employed as their court sculptor; his name disappears from the ducal accounts after 1510, and other sculptors took his place at court.

The facility with which Crocq has carved the figure of Saint John and the attendant details is staggering, from the alternating crescent-shaped curls of his hair, the folds of the mantle, the distinctive raised cuticle around the nails, to the soft, ridged spine of the book. The gaze of the lamb upwards is also exquisitely realised. Estimated at £200,000-300,000, the sculpture comes to the market from a Belgian private collection.

Attributed to Jan Crocq (active 1486-1510), Saint John the Baptist, French, Lorraine, Nancy or Bar-Le-Duc, circa 1500-1510. Tonnerre limestone, 163 by 59 by 40cm., 64 1/8 by 23¼ by 15¾in. Estimate: £200,000-300,000. Photo: Sotheby's

Provenance: by repute the Sainte-Chapelle, Hôtel de Ville, Dijon;

certainly Mr. E. Ingels, Belgium, late 19thcentury;

with Joseph Brummer, Paris, circa 1910;

William Rockhill Nelson, Oak Hall, Kansas City, Missouri, before 1915;

thence by bequest to The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, 1915 (later known as The William Rockhill Nelson Collection and from 1983, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), inv. no. 33-69;

sold by order of the University Trustees of the William Rockhill Trust, Sotheby’s New York, 1 June 1991, lot 18, as 15thcentury style;

private collection, Belgium

Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City, 1933, p. 72 (attributed to Claus Sluter);

The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, Kansas City, 1941, p. 89, fig. 8;

The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, Kansas City, 1949, p. 112 (school of Burgundy, late 14thcentury);

Handbook of the Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum, Kansas City, 1959, p. 54 (School of Burgundy, late 14thcentury).

Notes: The present statue is one of only a handful of monumental stone carvings from the fabled workshops active in the Burgundian Netherlands in private hands. Saint John the Baptist was part of the collections of Joseph Brummer and William Rockhill Nelson and survives in good condition. It relates to specific works by a sculptor active at the large ducal court in Nancy and was once part of an important altarpiece: possibly that in the chapel of the town hall of Dijon, as Brummer suggested.

At the end of the 15th century, Rene II (1473-1508), Duke of Bar and Lorraine and King of Sicily, led his territory through its second resurgence in 100 years. He created one of the most powerful economies in Europe and consequently paved the way for one of the great transitional artistic patronages of the late Gothic era. The Duke asked talented local and foreign artists to join his court and they created a seminal style that combined Netherlandish, Rhenish and Italian influences. Its chief proponent was the Northern sculptor Claus Sluter. His work was already a century old but Sluter's monumental figures for the Well of Moses in the Chartreuse at Champmol and the tomb of Philip the Bold in Dijon still influenced the region's artistic production. Particularly the cool, stern facial types employed by Sluter and the volume of the drapery persisted. However, the style was updated with elaborate passages of drapery and hairstyles. Figures became more elongated and were set less firmly on the ground, appearing more dynamic and elegant.

The most important sculptor active at the Bar and Lorraine court was Jan Crocq, who, like Sluter, came from the Low Countries. He is recorded as working on several commissions in the ducal palaces and chapels and rebuilt sumptuous tombs for Rene's ancestors. None of his documented work survives but pre-Revolution sketches of the tombs have revealed some stylistic traits, prompting scholars to attribute a body of work to Crocq. A wonderful limestone Saint Catherine in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (inv. no. 07.196) compares most closely to the present sculpture. The faces of both figures are characterised by a nose with a long bridge and wide nostrils and similarly shaped lips. Despite the difficulty in comparing the downcast eyes of Catherine with the straight gaze of John, the proportions of the eyes are the same. John's hair consists of alternating crescent-shaped curls which also make up the beard of the trampled Emperor Maxentius in the New York group. The mantles of the statues are arranged in analogous triangular folds, the same zig-zag texture decorates the inside of the fabric, and decorative borders with beaded edges line the edges of the mantles of both saints. Compare also the execution of the drooping sleeves of Saint John and Maxentius. The hands of both Saint John and Catherine have long fingers placed in carefully studied positions and have a distinctive raised cuticle around the nails. Both hold a book with a soft, ridged spine. Despite some losses to the base of Saint John, it seems that it too had a octagonal base over which certain details, such as the camel's head and foot of Saint John, and Maxentius in the Metropolitan Museum's statue, projected. Furthermore the figures could have been from the same ensemble because they are of comparable height: 163 and 156 centimetres.

Two wood sculptures representing Saint George and Saint John the Evangelist in the Musée Lorrain in Nancy, illustrated by Bouchot (op.cit.), also have the "crescent" curls seen in the present sculpture's hair. The Evangelist in particular has a comparable drapery scheme with creases radiating from the saint's waist and triangular folds to one side.

According to archival research carried out by Maxe-Werly in 1897 (op.cit.) in the ledgers of the Guild of Saint Luke in both Bruges and Antwerp, Jan Crocq was a native of Flanders and probably born in Antwerp. The archives refer to him as Jan Croc, Croec, or Crook and explain that he was active during his early career as an engraver and carver of wood ornaments. In 1487 he appears in the town records of the city of Bar, receiving payment for the restoration of the tomb of Henri of Bar in the Church of Saint Maxe and a chimney piece in the ducal palace there. A letter from 20 June 1488, signed by Duke Rene II, tells him that he can count on continuous commissions from the Duchy of Bar and Lorraine provided that he remains in Bar. In 1489 he was working in Rheims cathedral on the chapel of Saint-Lait. From 1499 to 1510 he received regular payments from Rene II and his wife, Duchess Philippe of Guelders, suggesting he was still permanently employed as their court sculptor. During this period he designed and executed the tomb of Charles le Temeraire in the college of Saint George (1506, now destroyed). Towards the end of this period, from 1508, he also received a subsidy for an apprentice called Francois Bourree. Crocq's name disappears from the ducal accounts after 1510 and other sculptors took his place at court.

In the early 1990s it was suggested that the present sculpture was perhaps a much later carving emulating the sculpture of Claus Sluter. The removal of a layer of paint, the identification of the stone, and new research with regards to the dating of the figure have determined it dates to the first decades of the 16th century.

A technical report by F. Robaszynski: Elements en vue de cerner l’origine de la pierre ayant servi a sculpter une statue de Saint Jean-Baptiste, Faculté Polytechnique de Mons, Belgium, dd. 12 March 1998, suggests the stone was quarried at Tonnerre, near Dijon, is available from the department.

RELATED LITERATURE: L. Maxe-Werly, 'Jean Crocq de Bar-le-Duc, sculpture et sa famille 1487-1510',Memoires de la Societes des Lettres de Bar-le-Duc, 1897, pp. 7-70; H. D. Hofmann, 'Der niederlaender Jan Crocq, Hofbildhauer in Bar-le-Duc und Nancy. Sein lothringische Oeuvre (1486-1519)', Aachener Kunstblaetter, 1966, pp. 106-125; J. Steyaert (ed.), Late gothic sculpture, the Burgundian Netherlands, exh. cat. Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent, 1994; P. Simonin, 'Oeuvres de Jan Crocq. Sculpture neerlandais en Lorraine', Le pays lorrain, 84, 2003, pp. 194-196; G. Sismann, 'Saint Jacques le Mineur attribue a Jean Crocq', Estampille-Objets d'Art, 437, 2008; J. Bouchot, 'Jean Crocq, imagier lorrain. Nouvelle e perspectives', Le pays lorrain, 108, 2011, pp. 329-336