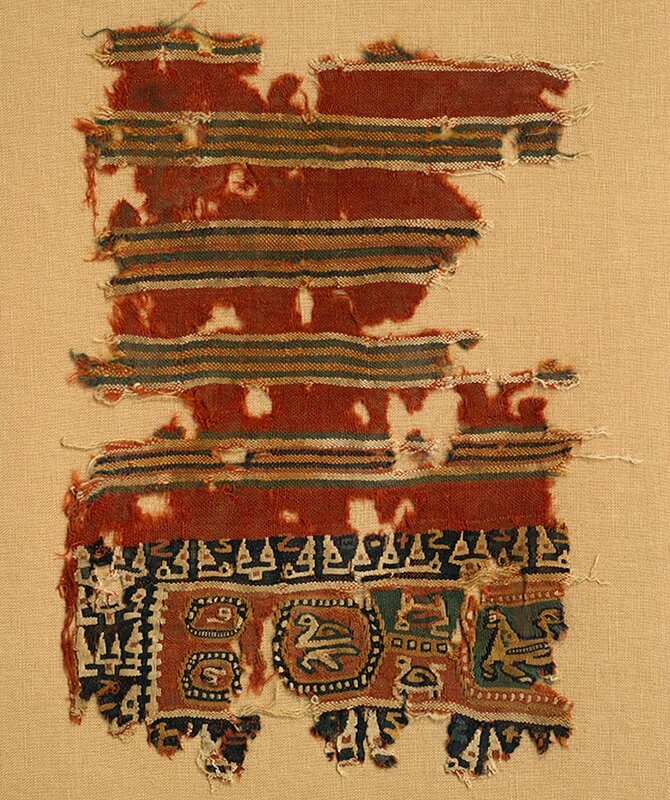

Qasab fragment with ducks and parrots Gauzy linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry Egypt Mid-11th century 980.78.111.A Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg.

TORONTO.- Cairo Under Wraps: Early Islamic Textiles, a Centennial exhibition on view at the Royal Ontario Museum, highlights the ROM’s collection of early Islamic textiles, dating largely from the 8th to 12th centuries. More than half of the exhibition’s approximately 80 fabrics are on public display for the first time and many of the oldest were collected by C.T. Currelly, the ROM`s founding director. These rare, delicate objects are displayed alongside ceramics, glass, metalwork and coins from the ROM’s permanent collection of Islamic art.

Cairo Under Wraps looks at Islam’s early history and culture through textiles from the first six centuries of Muslim rule. The exhibition illustrates that while earlier civilizations used human figures to convey religious and political messages, Islam used Arabic script as a means of communication and as a primary symbol of the new religious faith. On display are “tiraz” textiles, some of which recorded historical information such as a ruler’s name, date, and place of manufacture. Others conveyed simple expressions of religious faith or simulated Arabic script for decorative purposes.

Exhibition highlights include a rare linen tabby fragment decorated with in-woven silk and gold tapestry bands. Likely the end of a turban cloth, the rope-like design running through the decorative band was highly popular in Egypt inthe 12th century. Other notable objects include a linen tabby with silk tapestry decoration dating to mid- 11th century Egypt that features Arabic letters transformed into Nilotic boats, and a stonepaste bowl from late-11th century western Syria decorated with a seated musician dressed in a garment with tiraz bands.

Knowledge about textiles from the early days of Islam comes mainly from Egypt, where fragile materials, including linen, cotton, wool, and silk have been preserved in the dry soil as burial shrouds. These luxury fabrics were likely first used as clothing (such as turbans and robes) and furnishing fabrics (such as curtains and cushion covers). These textiles tell the story of Islam’s far-reaching global trade and taste for high-quality luxury goods.

The exhibition is curated by Anu Liivandi, Assistant Curator (Textiles & Fashions); Dr. Karin Ruehrdanz, Senior Curator (Islamic Decorative Arts); and Dr. Lisa Golombek, Curator Emeritus (Islamic Art).

Cairo Under Wraps is on display until January 25, 2015 in the Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles & Costume. The exhibition shares the gallery with Fashion Follows Form: Designs for Sitting, featuring fashions from Toronto-based designer Izzy Camilleri whose IZ Adaptive designs are among the first in the world created exclusively for women and men who use wheelchairs. Displayed with Camilleri’s designs are 18th and 19th century fashions from the ROM’s renowned collection, also created for a seated, L-shaped body.

Cairo Under Wraps: Early Islamic Textiles

What we know about textiles from the early days of Islam comes primarily from Egypt, where fragile materials—linen, cotton, wool, silk—have been preserved in the dry soil as burial shrouds.

This exhibition displays t extiles from the first six centuries of Muslim rule, mostly made in Egypt but also imported from other quarters of the Muslim world — Iraq, Iran, and Yemen. The textiles tell a story of wide-ranging global trade and a taste for high-quality luxury goods.

Some of the material on display was collected by Charles Trick Currelly, the founding director of the ROM. In this our centennial year, which is also the year that another major cultural institution — the Aga Khan Museum — will be opening in Toronto, we celebrate by featuring the ROM’s collection of Early Islamic textiles.

Ikat shawl with embroidered inscription. Cotton tabby with warp ikat pattern and embroidery, Yemen, 10th century, 963.95.9. Royal Ontario Museum

This shawl has warp ikat patterning of splashed arrows arranged in 15 panels by white warp stripes. The bottom has a twisted warp fringe. Near the fringe is a single word (undeciphered) in tiny letters. The embroidered kufic inscription repeats: 'In the name of Allah; dominion belongs to Allah.'

Ikat shawl with painted inscription. Cotton tabby with warp ikat pattern, ink, gold leaf, Yemen, 10th century, 970.364.19. Royal Ontario Museum

This example has warp stripes in brown, blue and white, typical of the famous medieval ikats from Yemen. Areas of colour with fuzzy contours are telltale signs of ikat. Across the width, a gold leaf inscription outlined in black ink exhibits a flamboyant floriated and plaited kufic style. To the right of the inscription is a complex knot. The text reads: 'In the name of Allah, may Allah bless Muhammad.'

Fragment of a shawl or turban cloth. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Dumyat (present day Damietta), Egypt, 1021-1022, 970.364.2. Royal Ontario Museum

The scale of decoration, the gauzy weave of the ground fabric, and the fringe at the bottom are typical of either a shawl or turban cloth. The inscription repeats on either side of a trellis pattern band, beginning at opposite ends. The Arabic letters have narrow staves that end in wedges. Wispy tendrils spring from the letters or float in the background. A tiny, illegible inscription rides the crest of the inscription band.

Monumental tiraz inscription. Gauzy linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 952–976, 963.95.5. Royal Ontario Museum

This inscription begins with the Basmala (In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate) and the first words of the title of the Fatimid Caliph, al-Mu‘izz (952–976). The kufic letters have terminals resembling leaves and tendrils. Letters which normally form an arc below the baseline are carried upward, taking the shape of a swan’s neck (the nun at the end of the word, al-rahman)Inscription: Bismi [llah] al-rahman al-rahim Ma‘add Abu [Tamim ...].

Tiraz fragment. Glazed linen tabby with silk embroidery, Iraq, 907 - 933. 978.76.67 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

Letters are carefully designed to fit into one another, like pieces in a puzzle. The calligrapher has also added leaves and transformed some letters into flowers. Inscription: [blessings...]...to Abd Allah Jafar al-imam al-Muqtadir billah, Commander of the Faithful, may Allah support him, from what was ordered by the vizier [Ali?]...

The Coptic Legacy

Christian Egyptians were known as Copts. They continued to dominate the textile industry after the Muslim conquest of Egypt, working in the materials and techniques most familiar to them. Imported silks from Sasanian Iran and Byzantium, woven on the drawloom, were copied in linen and wool using the much simpler technique of tapestry-weaving.

The production of textiles under Muslim rule saw Coptic weavers gradually adapt to the new tiraz style. Familiar with Roman and Byzantine designs, they were responsible for introducing these into the Islamic art of Egypt. Often the imagery includes Christian motifs, such as the cross or figures with arms held out in prayer (orans).

Generic hunting scene. Linen and wool tapestry, Egypt, 4th - 5th century. 910.131.36. Walter Massey Collection. Royal Ontario Museum

Hunting motifs and inhabited plant scrolls appear frequently in Roman art, denoting abundance and prosperity. This Coptic tapestry is also given an early date because of its classical motifs, naturalistic proportions, attempts at perspective and lively movement

Praying saint. Linen and wool tapestry, Egypt, 7th - 8th century. 980.78.27. Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

A female saint wearing elaborate Byzantine court dress is depicted with a halo and both arms raised in prayer. The static frontal pose and greater degree of abstraction are characteristic of a date after the Arab conquest.

Leopards flanking a tree. Wool and linen tapestry, Egypt, 8th - 9th century. 978.76.136 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

Judging by similar pieces in other collections, this is part of a hanging with roundels containing four animals flanking a stylized tree. It shows the influence of contemporary drawloom-woven silks with reverse repeats

Castor and Pollux at the hunt. Linen and wool tapestry, Egypt, 5th century. 910.131.8. Walter Massey Collection. Royal Ontario Museum

This inscription begins with the Basmala (In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate) and the first words of the title of the Fatimid Caliph, al-Mu‘izz (952–976). The kufic letters have terminals resembling leaves and tendrils. Letters which normally form an arc below the baseline are carried upward, taking the shape of a swan’s neck (the nun at the end of the word, al-rahman)Inscription: Bismi [llah] al-rahman al-rahim Ma‘add Abu [Tamim ...].

Pseudo-inscription and medallion band. Linen tabby with wool tapestry Fayyum, Egypt, 9th century. 975.403.5. Royal Ontario Museum

Hexagonal medallions containing a bird alternate with pairs of leaves. The simple kufic-style band below simulates Arabic script, inspired by tiraz textiles

Crowned female figure from a hanging. Wool and linen tapestry, Egypt, 7th - 8th century. 980.78.6; Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg Royal Ontario Museum

The mural crown identifies this as a Roman city goddess and the finely modelled features reflect the naturalism of Roman painting. However, the garment trimmed with bands of drawloom-woven silk and the jewelled necklace draw inspiration from later Sasanian and Byzantine art.

Band with floral roundels. Linen and wool tapestry, Egypt, 7th - 8th century. 910.130.15. Walter Massey Collection.

This band was probably used to trim a garment, as depicted in the previous example. The design has been inspired by slightly later silks in which the roundels are larger and woven in several colours.

Band with ibex and birds surrounding a tree. Wool and cotton tapestry, Egypt or Iraq, 7th - 9th century. 970.364.10. Royal Ontario Museum

Panels with highly stylized ibex and addorsed (back-to-back) birds recall Sasanian silks. The ibex wears a jewelled neckband with floating ribbons, symbolic of royal ownership. The use of cotton instead of linen is more characteristic of West Asia than Egypt at this early date.

Inhabited scroll. Wool tabby with wool and linen tapestry, Egypt, 8th - 10th century. 910.129.54 Walter Massey Collection. Royal Ontario Museum

The plant scroll framing birds and animals is familiar from earlier examples, but the linear quality of the plant and the elongated compartments it forms are characteristic of a date after the Islamic conquest

Royal figures. Linen and wool tapestry, Egypt, 8th - 9th century. 980.78.104 .Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The material and technique are particularly fine, but the extreme abstraction of the style makes it difficult to identify the motifs — apparently a royal figure with attendants, framed by a pearl border.

Long-legged birds in pearl roundels.Wool and cotton weft-faced compound twill, Iran or Iraq, 7th - 9th century. 970.364.12.Royal Ontario Museum

This drawloom-woven textile shows the influence of Sasanian silks with birds or animals in pearl roundels. The bird would face the opposite direction in adjacent roundels, The design is actually white on a red ground, but we show the reverse because it is in better condition

Camels and stars. Linen tabby brocaded in wool, Egypt, 8th - 9th century. 974.171.12. Royal Ontario Museum

Rare examples of brocaded decoration are difficult to date because they are so different in style and consist largely of simple geometric motifs. An example in Antwerp has been radiocarbon dated to the 8th - 9th century, well after the Arab conquest.

Lions in plant scroll. Linen and wool tapestry Bahnasah, Egypt, 9th century.978.76.132. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The inhabited plant scroll, a motif popular throughout the Roman Empire, was later incorporated into the tiraz bands of Muslim Egypt. This piece relates to a textile with an inscription mentioning the tiraz at Bahnasah, the major city of the Fayyum, and a date c. 850.

Tiraz fragment with Christian motifs. Gauzy linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 952–976. 963.95.5. Royal Ontario Museum

This inscription begins with the Basmala (In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate) and the first words of the title of the Fatimid Caliph, al-Mu‘izz (952–976). The kufic letters have terminals resembling leaves and tendrils. Letters which normally form an arc below the baseline are carried upward, taking the shape of a swan’s neck (the nun at the end of the word, al-rahman)Inscription: Bismi [llah] al-rahman al-rahim Ma‘add Abu [Tamim ...].

Tiraz band from a striped garment. Wool tabby with wool and cotton tapestry Fayyum, Egypt, 9th - 10th century, 980.78.43. Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

A rectangular tapestry-woven panel with birds and quadrupeds in pearl medallions is set into a ground decorated with multicoloured weft bands. The panel is framed by a tiraz-like inscription in Fayyumi pseudo-Arabic script, in which the vertical staves take on a pine-tree shape.

Abbasid & Early Fatimid tiraz

Abbasid tiraz Arrival of the Fatimids in Cairo

The first Muslim dynasty, the Umayyad, fell to the Abbasids in 750, and the capital moved from Damascus (Syria) to Baghdad (Iraq). Here the Abbasid Caliph ruled an empire stretching from North Africa to Afghanistan. The Caliph’s display of wealth and court ceremonial was on a par with that of the Byzantine Emperor. The textiles shown here were both imported into Egypt from the east and produced at home.

The calligraphic style prevails

The style of kufic is calligraphic, resembling the artistry of contemporary Qur’ans. However, because these inscriptions are decorative, the calligrapher took liberties with the script, inserting superfluous strokes and flourishes to create rhythm and pattern.

Tiraz fragment. Glazed cotton tabby painted in ink, Iraq, 11th century,975.403.3. Royal Ontario Museum

This painted inscription is in the style of the finely embroidered tiraz imported into Egypt from Iraq While the letters appear identifiable, a complete reading of the inscription has yet to be done. Over the final letter (on the left) a small inscription appears, possibly the name of the calligrapher.

Tiraz fragment. Glazed cotton tabby with silk embroidery, Iraq, Early 10th century, 963.95.7. Royal Ontario Museum

The elongated vertical letters create a pulsating rhythm. Many superfluous letters, such as the crescent-shaped tails below the script, make reading difficult. Inscription: In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate. My support is in Allah alone. In Him I put my trust (Qur’an ll:87) power and beatitude and piety. May Allah bless Muhammad ...the prophet [...] Allah and grant peace […] Allah [...]

Tiraz fragment. Glazed linen tabby with silk embroidery Tinnis, Egypt. Dated AH 299 (911 - 912), 978.76.18. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

Written in a clear, unadorned kufic, the inscription contains much historical information. The name of the Caliph is missing, but it mentions the vizier, Abu al-Hasan Ali, son of Muhammad, who commissioned the garment, the official Shafi, the date AH 299, and the workshop (Tinnis)..

Tiraz fragment. Glazed linen tabby with silk embroidery, Baghdad, Iraq. Dated AH 300 (912 - 913), 978.76.400. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

In this artistic rendering of simple kufic, the vertical staffs are elongated but there are no superlative flourishes. The inscription names the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir and identifies the place of manufacture as Baghdad (called Madinat al-Salam, “City of Peace”). The artist signed his name above the final words: Muhammad, son of Abbas.

Tiraz fragment. Mulham with silk embroidery, Iraq, 10th century, 963.95.8. Royal Ontario Museum

Mulham was highly prized because the combination of a fine silk warp and cotton weft produced a soft, smooth, tightly-woven fabric. The inscription in calligraphic kufic has elegant, carefully spaced vertical letters. Some tall letters have even been inserted into words that do not require them. Inscription: [May Allah bless the Prophet Muhammad] Seal of the Prophets, and all the members of his family, the good, the virtuous. Blessing from Allah, and grace, peace and happiness [to the Caliph...]

Tiraz fragment. Glazed linen tabby with silk embroidery, Egypt. Dated AH 304 (916 - 917), 978.76.42 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

In Egypt, the embroiderer used to pull a thread to mark the ground line of the inscription, but guideline stitches marking the height of the letters, as seen here, are rarely left in the finished product. The dated inscription names the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir, and the vizier Ali, son of Isa who ordered it, and Shafi who carried out the order.

Tiraz fragment. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 996 - 1021, 978.76.83. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The bold form of kufic with thick letters, from which the rising tails of certain letters are swept upward in a swan’s neck curve, follows the style of embroidered inscriptions of the Abbasid period.

The inscription mentions the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, but most of the words have been lost.

Kufic inscription in reserve on a boat-shaped panel.Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, c. 1000, 970.364.15.Royal Ontario Museum

This attractive inscription band contains only two words, repeated over and over: Success through Allah (wal-tawfiq billah). The rhythm is carried by the repetition of the rising tails of the letters qaf and waw. Vertical staffs are tied together by horizontal bars.

Embedded scripts

Embedded scripts

During the later Fatimid period more attention was paid to embedding the inscription within an artistic background. Tendrils grow from the letters and sprout buds (floriated kufic). Intricate arabesque designs of rhythmically scrolling and interlacing foliage often frame birds and animals.

Common repertoire of popular motifs

Many elements making up the decorative bands that accompany tiraz inscriptions since the 11th century and eventually dominate them are not specific to textiles but are equally employed in other media. Among the frequently featured birds and animals was the hare or rabbit. Its popularity in the Early Islamic period may be due to positive associations such as prosperity, fertility, and clever handling of difficult situations.

Tiraz fragment. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 12th century, 963.95.13.Royal Ontario Museum

The central band has rows of lozenges containing winged animals, birds, and kufic motifs. The inscription bands framing it have vertical staves, regularly repeated, between which are single leaves enclosed within a scroll. The inscriptions repeat a single word, possibly 'power'.

Tiraz fragment.Glazed linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, Late 11th century. Royal Ontario Museum

The familiar tripartite band consists of inscription in mirror image around a figural band. The additional epigraphic bands above and below do not have a coloured background but have rosettes situated between the vertical staves. Below the line runs a series of tails derived originally from the kufic low letters but meaningless in this context.

Tiraz fragment with palmettes. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, Late 11th century, 978.76.106. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The pseudo-inscription appears against a solid yellow ground suggestive of gold and is bordered by a palmette design.

Tiraz fragment with hares. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, mid-11th century, 970.117.2. Royal Ontario Museum

The background of the kufic inscription flanking the decorative band shows the formation of arabesque designs in the spaces between the tall vertical letters. The interlocking medallions of the inner band contain hares and the outer bands contain spotted winged quadrupeds.

Tiraz fragment with birds. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 996 - 1021. 978.76.551. Royal Ontario Museum

Pairs of confronted birds occupy the decorative band between two kufic inscriptions that name the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim (ruled 996-1021).

Tiraz fragment with foliate background. Bleached cotton tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 1020-1036, 980.78.50. Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The white letters of the inscription stand out against a blue ground, filled with undulating green tendrils. Some of the letters are braided together. The inscription names the Fatimid Caliph al-Zahir (ruled 1020-1036).

Monumental tiraz inscription. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 78.76.170. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg.

The letters of the inscription (illegible) are contracted to make space for the trellis pattern in the background. Below the inscription line are what appear to be extensions of the Arabic letters that descend, but they seem to have been whimsically transformed into Nilotic boats with prows extending to the right.

Monumental tiraz inscription.Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, mid-11th century, 978.76.436. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The letters are woven in green silk, outlined in black, against a trellis background.

Tiraz fragment with leopards and floriated kufic. Glazed linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 1020- 1036, 978.76.195..A Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

Although little remains of the inscription, the titles of the Fatimid Caliph al-Zahir provide a date. Delicate tendrils spring from the letters and sprout tiny trefoil leaves. Two narrower bands contain spotted striding quadrupeds (leopards).

Tiraz fragment with honeycomb background. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 1000-1050?, 978.76.1084. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The illegible inscription lies in front of a honeycomb background.

Gold!

All the textiles (qasab) in this section have tapestry decoration in silk and gold and represent expensive, luxury fabrics. Gold could only be obtained through the government monopoly, so these beautiful textiles must have been made for the royal household or the aristocracy. Most do not bear the name of the ruler or date. The inscriptions are barely legible and are meant simply to convey good wishes on the owner.

Qasab fragment with ducks and parrots. Gauzy linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry, Egypt, Mid-11th century, 980.78.111..A Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

This very sheer green linen tabby has three tapestry-woven bands with gold decoration. The roundels in two of the bands contain ducks alternating in direction while the third band has large parrots standing on vines. The inscription, which floats in the gold ground above and below the ducks, is illegible.

Qasab fragment. Linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry, Egypt, 11th century, 978.76.496. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg.Royal Ontario Museum

This blue gauzy linen has two tapestry-woven bands, both with kufic inscriptions framing a row of tangent cartouches. Much of the detail is worked in gold, although most has disappeared. The inscriptions are not legible but may have contained the Fatimid caliph’s name.

Qasab fragment with ducks and parrots. Gauzy linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry, Egypt, Mid-11th century, 980.78.111..A Wilkinson Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

This very sheer green linen tabby has three tapestry-woven bands with gold decoration. The roundels in two of the bands contain ducks alternating in direction while the third band has large parrots standing on vines. The inscription, which floats in the gold ground above and below the ducks, is illegible.

Qasab fragment.Linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry, Egypt, 11th century, 963.95.14. Royal Ontario Museum

Delicate tendrils sprout from the gold inscription of this once rich textile. Not enough remains of this fragment to allow a reading of the tiraz protocol.

Tiraz fragment.Glazed mulham, ink, gold leaf, Iran, 10th century, 963.95.3. Royal Ontario Museum

Mulham is a particularly fine tightly-woven fabric with a silk warp and cotton weft. It was considered luxurious, as it was a half silk. Mulham was mentioned by contemporary historians as a product of the cities of Merv, Khurasan, and Isfahan.

The words “There is no God but Allah” was printed in black ink, repeated five times. The printing block was not carefully aligned while making the repetition. Gold leaf was then laid down within the black outlines.

Cursive script

By the 12th century, the archaic kufic script gave way to the cursive style (naskhi). Inscriptions no longer communicate the protocol of the Fatimid caliph. Instead, the words convey general wishes for success and well-being. The decorative bands between the two inscription lines become wider and denser.

Blue tiraz fragment. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 12th century, 978.76.197. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

Birds and hares occupy the spaces formed by the rope-like grid, woven into the pale blue linen ground. The cursive inscription repeats the generic Arabic text, “Victory from Allah.”

Tiraz fragment. Glazed linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, Mid-12th century, 961.107.3. Royal Ontario Museum

Four cursive (naskhi) inscriptions repeat the phrase: “Good fortune and prosperity.” The rope-like interlace of the decorative bands encloses pairs of birds and hares. The yellow silk ground imitates the more expensive gold-wrapped thread found in the other fragment.

Tiraz fragment. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Egypt, 12th century, 978.76.990. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg.Royal Ontario Museum

In the 12th century, tiraz bands grew wider and were more heavily decorated. This elaborate example has exceptionally wide bands, making it more appropriate for furnishings than for clothing.

The birds, hares, winged quadrupeds, and plant motifs in the interspaces are so abstract as to be almost unrecognizable.The cursive (naskhi) Arabic inscription expresses a wish for good fortune and prosperity.

Qasab fragment, perhaps the end of a turban cloth. Linen tabby with silk and gold tapestry, Egypt, 12th century, 978.76.188. Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The rope-like design that fills the decorative band was very popular in this period. Hares appear in the interspaces and in the cartouches of the narrow bands above and below. The rich gold ground is woven with gold wrapped around a silk core.

The Arabic text repeats: 'Victory from Allah to the servant of Allah'.

Regalia

As in other medieval societies, there were rights that belonged to the caliph exclusively; being mentioned in the sermon when the Muslim community gathered on Fridays was one of them. It expressed the recognition of the named person as sovereign. Hence, a change in power – whether by regular succession, conquest, or usurpation – would be first announced at this occasion.

Shawl fragment with large kufic tiraz bands. Linen tabby with silk tapestry, Misr (Old Cairo), Egypt, 927-928, 978.76.985, Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The inscription names Ali, son of Isa, the well-known vizier of the Caliph al-Muqtadir bi-llah, as the one who ordered the textile from the private factory of Misr (present day Cairo). It also names the superintendant of the tiraz, Shafi al-Muqtadiri. However, the name of the Caliph himself has not survived.

Everyday life

Vessel stamps

Vessels to measure all kinds of everyday commodities carried stamps confirming the accuracy of volume or weight. In Umayyad and Abbasid times, the name of the official overseeing the manufacture of certified measures was usually introduced in the inscription on glass stamps with the formula, “ala yaday” (literally, “under the hands of”). This is the same formula used in inscriptions on tiraz textiles.

Globular jar. Earthenware, thrown, slip-covered, glazed, with splashes, Egypt, c. 975-1025, 908x25.55. Royal Ontario Museum

As in other areas of the Islamic world, pottery making in Egypt soon developed into an art for everyday life, driving technical invention. A colourful type among the early production is splashed ware. In this case, the effect was achieved by applying copper-green and manganese-purple splashes to the transparent lead glaze over the off-white slip. From the 9th century onwards, the colour scheme yellow-green-purple became popular all over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Tall-necked saucer lamp. Earthenware, thrown, modeled and glazed, with splashes, Egypt, c. 1100, 908.21.24. Royal Ontario Museum

Oil lamps were made using several different parts. Spout and handle were attached to the bowl containing the oil, and the part covering the bowl was probably also made separately. Together with the tall flaring neck, it protected the oil from spilling and impurities. This lamp is covered in light green glaze with added splashes of purple. Its most interesting aspect, however, is the second spout that would allow the lamp to shed more light.

Saucer lamp. Earthenware, thrown, modeled and glazed, Egypt, 12th century, 908.21.30. Royal Ontario Museum

A somewhat simpler variety of the saucer-shaped lamps, this one displays a low neck. A transparent lead-glaze is applied over a slip.

Sherd with kufic inscription. Stonepaste, thrown, with opaque glaze and lustre paint, Egypt, 1025-1075, 909.37.9. Royal Ontario Museum

What is left of a monumental kufic inscription stands out in reserve against the lustre-painted background. The writing preserved on this sherd reads, al-mulk, which has many meanings, from ‘kingdom’ to worldly possessions in general. It appears often in the saying, al-mulk lillah: ‘The kingdom belongs to God.’

Tall-necked lamp with feline handle. Earthenware, thrown, modeled and glazed, Egypt, c. 975-1075, 908.21.17. Royal Ontario Museum

Glaze did not completely oust moulded decoration but forced it to become larger and more visible. Several knobs were applied to this lamp and the neck was crenellated making the opening look like a flower. Giving the handle the shape of an upright standing feline recalls many small animal figures made of bronze that were popular in the Fatimid period.

Small jar.Stonepaste, thrown and glazed, Egypt, c. 1025-1075, 908x25.16. Royal Ontario Museum

The favourite glazes of the early period could also be applied as monochrome coatings. The potter’s disregard about the incomplete coverage of the manganese-purple glaze points to speedy production in large quantities. Such a small jar as this could be useful in the kitchen as well as for cosmetic purposes.

Plaque with carved tendril.Wood, carved and inlaid, Egypt, 10th - 13th century, 2007.29.6. In memory of Professor Rostislav Hlopoff; Certified Canadian Cultural Property. Royal Ontario Museum

The contrast in colour created by the use of different kinds of wood underlines the variation of the tendril. The palmette in the centre branches out symmetrically to both sides while around the darker frame, the half-palmette leaves sprout along a meandering tendril.

Filter for a water jug. Pottery, unglazed, Egypt, 11th century, 947.46.11. Royal Ontario Museum

Zigzag lines carved into the borders and dividers of filters are seen as hallmarks of Fatimid production. In this case, they can be found on all the stabilising dividers. Two of the perforated areas have a geometric design which can be read as a stylised flower.

Fragment with pseudo-kufic inscription. Glass, painted in brown lustre, Egypt, 12th century, 948.226.10. Royal Ontario Museum

With time, decorative effects created by beautiful writing – the rhythmical sequence of vertical strokes and rounded low letters or the upturned ends resembling swans’ necks – took on a life of their own. The repetition and graceful flow of letters, while not actual writing, suggested familiar well-wishing inscriptions to the viewer.

Glass weights

Early glass weights served to control the weight of individual coins. The abundance of later glass weights and their often rudimentary inscriptions have raised doubts, however. It is assumed, that they were employed, together with or instead of the more expensive bronze weights, to balance as many coins of various denominations as were needed in a particular transaction.

Glass weight. Moulded and stamped glass, Egypt, 1094-1101, 945.78.37. Royal Ontario Museum

This unusual, large, and heavy glass weight (8.5 g) corresponds to three times the average weight of a dirham (2.8 g). It was issued in the name of the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustali billah, AH 487-495 (1094-1101). The brown stained colourless glass was probably meant to indicate that this item replaced three dirham weights.

Glass weight.Moulded and stamped glass, Egypt, 1014-1020, 976.67.1. Royal Ontario Museum

Weighing 2.8 g, this blackish-blue glass weight was obviously intended to check a full dirham, although it lacks such explicit information. It was produced in the name of the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-amr Allah, who ruled from AH 386-411 (996-1020) and his son, Abd al-Rahim, designated heir for the period AH 404-11 (1014-21).

Coinage

Another such prerogative was coinage regality, the right to have coins minted in one’s own name. It was strictly enforced and, therefore, coins most exactly speak to historians about the extension of an area claimed by a ruler. In Egypt, the capital Misr (Old Cairo) — where the making of gold coins (dinars) started before the end of the 8th century — had the most important mint. Besides dinars, dirhams (silver coins) and copper coins (fals) were minted

Quarter Dirham (silver coin) of the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu’izz. Struck silver, Egypt, 953-75, 987.256.281. Royal Ontario Museum

Lacking place and date, this small silver coin probably reflects the turbulent period of the conquest of Egypt by the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu’izz lil-din Allah (953-75). His name encircles a central dot on the reverse. The profession of faith on the obverse remained without the Shi’ite component.

Early Islamic dress

In contrast to Coptic tunics, which were woven to shape on a very wide loom, these dresses are composed of several pieces cut from a length of fabric woven on a narrower loom. In general, the body is cut in a single piece that wraps over the shoulder to form the centre front and back of the garment. The sleeves and side panels are also cut so that they wrap around the body. Smaller pieces are often required to complete the garment, and their haphazard nature suggests reuse of an older garment. The earliest dresses are decorated with applied bands in coloured wool. Later, the decoration changed to bands of silk embroidery.

Man's shirt. Fine linen tabby trimmed in silk twill, Egypt, 8th - 12th century, 910.1.9. Royal Ontario Museum

This simple but beautifully shaped shirt is a rare and unusual piece. It is made of fine linen of uniform weave, luxuriously trimmed in silk around the neck opening and cuffs. Everything suggests that this was a high-end garment, but it is hard to find a comparable piece — especially with such bouffant sleeves. Elements like the narrow body and gently flared skirt are reminiscent of Sasanian garments, but nothing quite like this has survived. For now, this garment remains a bit of a mystery.

Coptic tunic fragment. Wool tabby with tapestry bands, Akhmim, Egypt, 6th - 7th century, 910.1.1 Walter Massey Collection. Royal Ontario Museum

This tunic was woven to shape in the classical manner. It represents less than a third of the final width: the tapestry band at the left edge is actually the remains of a mid-shoulder band (clavus). The tapestry decoration is integral, as is the distinctive looped weft fringe at the hem.

Child's dress.Linen tabby with inserted wool tabby and twill bands, Egypt, 8th - 9th century, 952.63 Gift of Dr. Elie Borowski. Royal Ontario Museum

The gently flaring, more fitted shape of this dress is similar to the adult garment in the case to your far right. However, this dress is composed of many more pieces: a front and back yoke, a skirt with centre and side seams plus triangular gores at the sides, and sleeves with 2-3 pieces under the arm. The deep vertically slit neckline and inserted contrasting bands are quite unusual and exceptionally attractive.

Child's dress. Linen tabby with silk embroidery, Egypt, 14th century, 978.76.1004, 1006, 1007, 1013 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The rest of the children’s dresses are all from the Mamluk period but reflect a style worn already in Fatimid times. All are wide in both body and sleeve, decorated with embroidered geometric designs in darning stitch worked on counted threads. Dresses with decoration confined to sleeve bands may be earlier than those with spaced stripes.

Child's dress. Linen tabby with silk embroidery, Egypt, 14th century, 978.76.1004, 1006, 1007, 1013 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The rest of the children’s dresses are all from the Mamluk period but reflect a style worn already in Fatimid times. All are wide in both body and sleeve, decorated with embroidered geometric designs in darning stitch worked on counted threads. Dresses with decoration confined to sleeve bands may be earlier than those with spaced stripes.

Child's dress. Linen tabby with silk embroidery, Egypt, 14th century, 978.76.1004, 1006, 1007, 1013 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The rest of the children’s dresses are all from the Mamluk period but reflect a style worn already in Fatimid times. All are wide in both body and sleeve, decorated with embroidered geometric designs in darning stitch worked on counted threads. Dresses with decoration confined to sleeve bands may be earlier than those with spaced stripes.

Child's dress. Linen tabby with silk embroidery, Egypt, 14th century, 978.76.1004, 1006, 1007, 1013 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

The rest of the children’s dresses are all from the Mamluk period but reflect a style worn already in Fatimid times. All are wide in both body and sleeve, decorated with embroidered geometric designs in darning stitch worked on counted threads. Dresses with decoration confined to sleeve bands may be earlier than those with spaced stripes.

Coptic child’s baptismal shirt. Cotton tabby embroidered in silk and silver lamella, Egypt, 19th century, 978.76.306 Abemayor Collection, Gift of Albert and Federico Friedberg. Royal Ontario Museum

This shirt is richly embroidered with both Christian motifs and Arabic inscriptions. Mary with the Christ Child is flanked by St. Macarius and an angel. A large Coptic cross is surrounded by four angels holding palm branches. Three military saints on horseback are identified as Saints Menas, Mercurius, and George.