![4]()

Florence and Herbert Irving. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

NEW YORK, NY.- Christie’s announced final details of the most anticipated auction for the Spring season of Asian Art: the sale of the private collection of Florence and Herbert Irving. Aptly titled Lacquer • Jade • Bronze • Ink: The Irving Collection, the sales pay homage to the materials the Irvings spent their lives studying and collecting. The collection will be sold across an Evening Sale on March 20 and a Day Sale on March 21, with a complementary online auction Contemporary Clay: Yixing Pottery from the Irving Collection from March 19 to 26. The full collection will be presented in a public exhibition from March 14-20 during Asian Art Week at Christie’s New York. Additional jewelry highlights will be included in the New York Magnificent Jewels sale on April 16, 2019.

From modest Brooklyn roots to the triumph that was the Sysco Corporation, the Irvings’ inspiring trajectory allowed them to build a better, more enlightened world. Their many contributions spanned major donations to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, including well over 1,300 works of Asian art, and underwriting acquisitions, curatorial positions, exhibitions, and galleries. In honor of the Irvings’ extraordinary generosity, The Met named the entirety of their Asian art galleries The Florence and Herbert Irving Asian Wing.

Their commitment to philanthropy is also seen across a network of charities, most notably New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, where the Irvings became the largest donors in its history. Together, the Irvings would pursue a massive philanthropic undertaking totaling over $1 billion in support and innumerable magnificent objects of art to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Columbia University Medical Center, and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, among other causes.

For Florence and Herbert Irving, the opportunity to live in dialogue with their extraordinary collection of Asian art and European decorative art was an incomparable experience. It was not enough to live surrounded by beauty; they felt obligated to share it with the world. Asian art, in particular, would become synonymous with the Irving name, as the couple came to amass one of America’s most significant private collections. From childhood days at the Brooklyn Museum to seeing their own names inscribed on the Asian art wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Irvings’ passion for art was a truly lifelong commitment.

Tina Zonars, Co-Chairman of Asian Art at Christie’s, comments: “Christie’s is honored to present Lacquer • Jade • Bronze • Ink: The Irving Collection, a grouping recognized for its remarkable quality and beauty. Carefully assembled across several decades, the Irvings created one of the foremost private collections of Asian art built upon scholarship and their personal passion. During their lifetime, the Irvings generously donated an extraordinary number of their treasured artworks to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The selection offered at Christie’s this spring encompasses their most valued objects which they chose to live with in their New York City home: exceptional Asian art set amongst elegantly appointed decorative arts. The March sales will offer the landmark opportunity for collectors to participate in the legacy of one of the leading private collections of Chinese, Himalayan, Japanese, and Korean works of art.”

![9]()

![3]()

Florence and Herbert Irving's interior. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

The Irvings’ Collecting History

The Irvings made their initial foray into collecting in the 1940s and 1950s. The glassware Herbert Irving acquired during the Second World War was joined by additional glass pieces and “reasonably priced” works by living artists. An eighteenth-century Chinese table, purchased in the early 1960s from the notable dealer Robert Ellsworth, was a harbinger of greater things. However, it was not until the autumn of 1967 that they discovered the possibilities of Asian art, when Mrs. Irving suggested a trip to Japan, and a friend encouraged the couple to visit the esteemed Alice Boney in Tokyo.

From their first acquisition in Tokyo, the Irvings wholeheartedly embraced Asian art. Mrs. Irving began to study the history of Chinese art, ceramics, and furniture at Columbia University, and attended lectures at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Through annual visits to Asia and in conversation with Boney, Ellsworth, and other dealers around the world, the Irvings honed their unique connoisseurial vision—one greatly aided by Mrs. Irving’s astute eye and enthusiastic scholarship. Behind the Irvings’ commendable acquisition strategy was a network of dealers and experts that came to feel like family.

The Irvings’ personal ties to dealers, curators, and fellow collectors grew in tandem with their collection. Each work, whether of masterpiece quality or more modest value, was viewed as an opportunity to develop connoisseurship. Throughout their journey in collecting, the Irvings were keen not only to acquire masterworks of Asian art, but also to build enduring relationships.

![5]()

Mr. and Mrs. Irving handling lacquer pieces in the National Palace Museum, Taipei in 1990.

Part I: Evening Sale (Lots 801-826)

The Evening Sale includes a curated cross-section of 26 of the best examples across the Irvings’ most collected categories: Lacquer, Jade, Bronze, and Ink, and some select ceramics. Featured lots include a highly important and extremely rare giltbronze figure of a multi-armed Guanyin ($4,000,000-6,000,000); an important and extremely rare Imperially inscribed greenish-white jade ‘Twin Fish’ washer ($1,000,000-1,500,000); a rectangular lacquer tray with decoration of autumn grasses and moon, Shibata Zeshin (1807-1891), Meiji period ($60,000-80,000); and Lithe Like A Crane, Leisurely Like A Seagull, by Fu Baoshi (1904-1965) ($800,000-1,200,000).

![2]()

![5]()

![8]()

![4]()

![6]()

![7]()

Lot 814. A highly important and extremely rare gilt-bronze figure of a multi-armed Guanyin, China, Yunnan, Dali Kingdom, 11-12th century; 14 7/8 in. (38 cm.) high. Estimate: $4,000,000-6,000,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Finely cast as a tantric image of Avalokitesvara (Guanyin) with three eyes and four arms shown seated with legs pendent, the primary hands held in anjalimudra, the other pairresting on the knees, wearing an elaborate, openwork crown, as well as beaded necklaces and other jewelry, and a dhoti tied with a sash below the waist, with two large pierced rectangular tenons projecting either side of the un-gilded upper back.

Provenance: The Pan-Asian Collection (Christian Humann, d. 1981), New York, by 1972.

Alice Boney, New York, 1983.

The Irving Collection, no. 871.

Literature: Anita Christy, "The Irving Collection: At Home in The Metropolitan Museum of Art," Orientations, November 1991, pp. 61-67, fig. 11.

Exhibited: On loan to the Denver Art Museum, 1972-1978, loan no. 77.1972.

Towards Enlightenment

A Superb Dali Multi-Armed Guanyin

Based on its similarity to a sculpture sold at Christie’s, New York, 24 March 2004, lot 77, which included an image of the Buddha Amitabha in the center of the crown, this compelling sculpture represents the bodhisattvaAvalokiteshvara, known in Chinese as Guanyin. (Fig. 1) The sculpture’s style indicates that it was produced in the Dali Kingdom (AD 937–1253), an independent state in southwestern China that was coeval with China’s Song dynasty (AD 907–1279) and more or less congruent with present-day Yunnan province. Dali sculptures are rare; the large scale, multiple arms, and unusual position in which the figure sits make this an especially rare and important example.

![2bis]()

Fig. 1 A gilt-bronze multi-armed Guanyin, Dali Kingdom (AD 937–1253); 13 5/8 in. (34.6 cm) high. Sold for 567,500 USD at Christie’s New York, 24 March 2004, lot 77.

A bodhisattva is a benevolent being who has attained enlightenment but who has postponed entry into nirvana in order to assist other sentient beings in gaining enlightenment. Richly attired, bodhisattvas are represented with long hair often arranged in a tall coiffure, typically with long strands of hair cascading over the shoulders, and often with a crown surrounding the high topknot. They wear ornamental scarves, dhotis of rich silk brocade, and a wealth of jewelry. Like Buddhas, bodhisattvas have distended earlobes; some wear earrings, others do not. Though generally shown barefoot, bodhisattvas may be shown wearing sandals, as in this sculpture.

Though usually depicted with a single head, two arms, and two legs, Guanyin—formally known as Guanshiyin Pusa—sometimes appears with multiple heads and limbs. The multiple heads and limbs indicate that the deity is able to assist more beings than can a deity with but one head, two arms and two legs. Though this sculpture originally sported additional arms—the original number is unknown—only four now remain. Separately cast, the additional arms were attached to the tenons that project from the backs of the upper arms. Two of the remaining arms are raised and clasped at the chest in a gesture of respect and reverence known as the anjalimudra; the other arms are lowered, the hands resting on the knees. The lowered left hand likely originally held a rosary, while the lowered right hand probably grasped a coiled rope or lasso as a lifeline to draw back to the path of enlightenment those who have gone astray.

Bodhisattvas generally are represented as standing but when shown seated are usually presented in the lotus position, or padmasana, with the legs crossed. By contrast, most Chinese images of Buddhist deities seated in “Western style”, or paryankasana, typically represent Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future. The presentation of this Guanyin in Western fashion immediately points to this sculpture’s origins in the Dali Kingdom. The alert, fully open, almond-shaped eyes that look directly outward also point to its origins in the Dali kingdom, as does the vertically set third eye that has been substituted for the traditional urna. In addition, the tall, cylindrical crown embellished with stylized, cursorily rendered clouds, the long, beaded necklace that descends to cross at the abdomen and then loops over the knees, and the low-waisted dhoti, which is secured at the hips, all signal this impressive sculpture’s origin in the Dali Kingdom, likely in the eleventh or twelfth century.

A twelfth-century bronze sculpture representing a two-armed Guanyin in the Yunnan Provincial Museum, Kunming, shares the same almond-shaped eyes that look directly outward, the low-waisted dhoti secured at the hips, and the long, beaded necklace that descends to cross at the abdomen and then loops over the knees as the present sculpture. (See Denise Patry Leidy, Donna Strahan, et al., Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, p. 140, fig. 100). A sculpture closely related in style, iconography, and general appearance in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (56.223) (Fig. 2) has been dated to the eleventh to twelfth century. (See Leidy and Strahan, Wisdom Embodied, pp. 138-40, no. 33).

![3]()

Fig. 2 A gilt-bronze multi-armed Guanyin, Dali Kingdom, 11th-12th Century; H. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm); W. 7 in. (17.8 cm); D. 4 3/8 in. (11.1 cm). Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1956, accession no. 56.223.© The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Robert D. Mowry

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus, Harvard Art Museums, and Senior Consultant, Christie’s.

![1]()

![1]()

![1]()

![1]()

![1]()

![1]()

Lot 806.An important and extremely rare Imperially inscribed greenish-white jade ‘Twin Fish’ washer, China, Qing dynasty, Qianlong incised four-character mark and of the period, dated by inscription to the cyclical bingwu year, corresponding to 1786; 10 in. (25.4 cm.) diam. Estimate: $1,000,000-1,500,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Finely carved with straight, flaring sides encircled by three bow-string bands, the interior carved in high relief with a pair of fish, the base raised on five rectangular feet surrounding an incised imperial poem, Ti hetian yu shuangyu xi (A Khotan Jade Twin Fish Washer), signed Qianlong yuti (imperially composed by Qianlong), dated to autumn of bingwu year (1786), followed by two seals reading guxi tianzi (Son of Heaven at Seventy) and youri zizi (Still Diligent Every Day), all picked out in gilding, the stone of pale greenish-white tone with subtle white flecks, hongmu stand.

Provenance: Sotheby Parke Bernet, Hong Kong, 28-29 November 1979, lot 405.

Ashkenazie & Co., San Francisco, 1982.

The Irving Collection, no. 392.

Literature: Sotheby’s, Sotheby’s Hong Kong - Twenty Years, Hong Kong, 1993, p. 295, no. 514.

Sotheby’s, Thirty Years in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2003, p. 328, no. 378.

Imperial Archaism and Harmony

A Magnificent and Rare Jade Washer with Paired Fish and Dated Qianlong Inscription

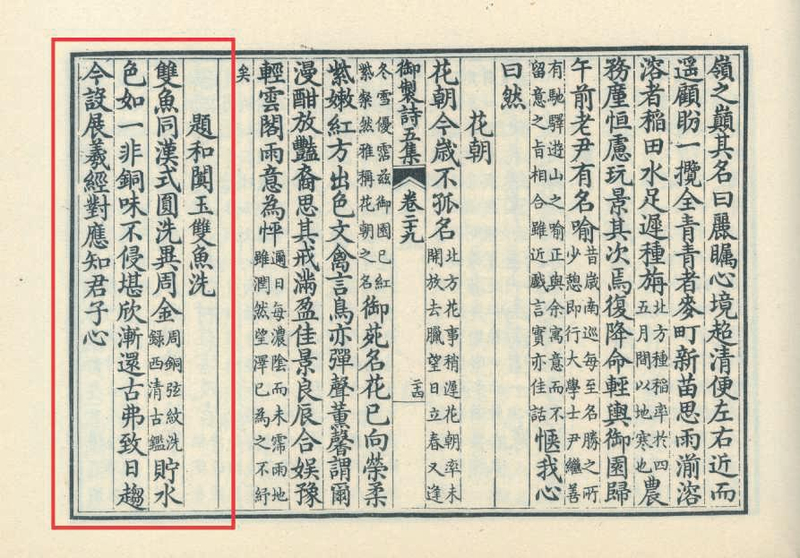

This exceptional imperial washer is of fine pale celadon-green jade and bears a four-character Qianlong mark on its base, encircled by a forty-character imperial poem. At the end of the poem is a date - autumn in the bingwu year of the Qianlong reign – equivalent to AD 1786. The poem reads:

Shuang yu tong Han shi, yuan xi yi Zhou jin, zhu shui se ru yi, fei tong wei bu qin, kan xin jian huan gu, fu zhi ri qu jin, she zhan Xi Jing dui, ying zhi jun zi xin.

This may be translated as:

“The pair of fish are in Han dynasty style,

The round washer differs from Zhou-dynasty bronzes.

Its colour is that of the stored water,

But not being metal it does not affect the taste.

Gradually returning to antiquity,

There is no need to hasten towards modernity.

If one were to open the Book of Changes,

One could understand the heart of a superior man.”

Qianlong bing wu run qiu yu ti (乾隆丙午閏秋御題 ‘Imperially inscribed in the autumn of the bingwu cyclical year’ [1786]

Two square seals follow the inscription – one has the characters in gold on the pale jade ground and the other, in reverse, has the characters reserved against a gilt ground. The seals may be read as: “Son of Heaven at Seventy” (guxi tianzi (古稀天子) and “Still Diligent Every Day” (youri zizi 猶日孜孜)). The Qianlong emperor had some 42 seals reading ‘Son of Heaven at Seventy’, and 24 reading ‘Still Diligent Every Day’. It is therefore not surprising to see these seals reproduced on a favored jade washer. The reign mark, the poem, the date and the seals on this washer are all carved and gilt on the base of the vessel. The text of the imperial poem is recorded in Complete Collection of the Imperial Poems of the Qing Emperor Gaozong (Qianlong) (Qing Gaozong (Qianlong) yuzhi shiwen quanji), Beijing, 1993, vol. 8, p. 713 清高宗 (乾隆) 御制詩文全集, 北京, 1993年, 第八冊, 頁713, where it is entitled: “A Khotan Jade Twin-Fish Washer” (Ti hetian yu shuangyu xi題和闐玉雙魚). (Fig. 1)

![1]()

Fig. 1 The imperial poem on the present jade washer, as documented in the Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji (Complete Collection of the Imperial Poems of the Qing Emperor Gaozong), Beijing, 1993, vol. 8, p. 713.

This washer is the largest of three known Qianlong jade washers of this form with two archaic-style fish carved on the interior. A small example (13.2 cm. diam.), apparently without an inscription, is in the Baur Collection, Geneva (see Pierre-F. Schneeberger, The Baur Collection –Chinese Jades and Other Hardstones, Geneva, 1976, no. B10); a somewhat larger, unpublished example is in a British private collection (17.8 cm. diam.); while the current example is the largest with a diameter of 25.5 cm. Like the present example, the washer in the private collection has low, neatly carved feet, but while the current vessel has five feet, this slightly smaller washer has four feet. The washer in the private collection also has the same imperial inscription and cyclical date.

The fish carved on these washers have been deliberately rendered in archaistic style, with the two fish carved side by side in high relief, and slightly under-cut, in a more formal style than is commonly seen on other jade pieces. As the inscription suggests, vessels with this type of twin-fish design are well-known in bronze from the Han dynasty, and there were a number of these bronze examples in Qianlong’s own collection. The Xiqing gujian 西清古鑑 illustrated six bronze washers with paired fish dated to the Han dynasty (see Xiqing gujian – Qinding siku quanshu 西清古鑑 欽定 四庫全, Shanghai, vol. 2, 2003, pp. 692-95). (Fig. 2) The Xiqing gujian is a 40-volume illustrated catalogue of ancient bronzes commissioned by the Qianlong emperor. It was compiled between 1749 and 1755 by Liang Shizheng (梁詩正1697-1763), Yu Minzhong (于敏中1714-1778) and Jiang Pu (蔣溥11708-1761) and includes some 1529 bronze objects from the imperial collection. The images in this catalogue exerted considerable influence on the form of jades commissioned by the Qianlong emperor.

![1]()

Fig. 2 A Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) bronze “twin fsh” washer documented in the catalogue of the Qianlong emperor’s bronze collection, Xiqing gujian, Shanghai, vol. 2, 2003, p. 694.

An extant Han-dynasty bronze basin with similar twin-fish decoration on its interior is in the Lee Kong Chian Art Museum, Singapore (see National University of Singapore, Lee Kong Chian Art Museum, Singapore, 1990, p. 306, no. 336). On this bronze vessel there is an additional short auspicious inscription, which appears between the fish. Like the jade washers, the bronze vessels depict both fish facing in the same direction – not head to tail as was often the case on other vessels. Bronze basins with similar fish apparently linked by a line – possibly to suggest a cord that would facilitate carrying them - have been found in tombs in Anhui and Jiangsu, dated AD 245 and 295 respectively (see Kaogu, No. 3, 1978, p. 155, fig. 3, and Kaogu, No. 11, 1984, pl. 3, fig. 6). Another similar bronze basin, now in the Liaoning Museum, with a design of a bird and a fish, rather than two fish, but in similar style (see Liaoningsheng bowuguan, Wenwu chubanshe, 1983, pls. 28 and 29), has an inscription dated to first year of the Yongxing period of the Eastern Han dynasty [AD 153].

This formal twin-fish motif was also applied to early ceramics. There is a small number of early Yue-ware basins, which were clearly inspired by the bronze vessels with paired fish. One of these is the Western Jin dynasty (late 3rd-early 4th century) basin in the collection of Sir Percival David (see Rosemary Scott, Percival David Foundation – A Guide to the Collection, London, 1989, p. 33, pl. 13). On the David Collection basin, the fish are joined at the mouth with an incised undulating line. There is another early Yue ware basin from the Ingram Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (see Mary Tregear, Catalogue of Chinese Greenware, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1976, no. 13), which has similar formal paired fish on the interior, but the fish on this basin are not joined by a line. Fish also occasionally appear on Western Han-dynasty cold-painted vessels, such as the 1st century dish preserved in the Yamato Bunkakan Museum, Nara (see Special Exhibition - Jixiang –Auspicious Motifs in Chinese Art, Tokyo National Museum, 1998, p. 66, no. 42).

The choice of fish as the motif to decorate the current imperial jade washer would not simply have been a reference to ancient vessels, but also to the meaning behind the depiction of fish. A source for the link between fish and harmony can be found in philosophical Daoism, specifically in the Zhuangzi 莊子, attributed to Zhuangzi, or ‘Master Zhuang’ (369-298 BC), who, after Laozi, was one of the earliest philosophers of what has become known as Daojia 道家, or the "School of the Way". Among other things, Zhuangzi consistently uses fish to exemplify creatures who achieve happiness by being in harmony with their environments. As part of a much more complex discussion in chapter seventeen (Qiu shui秋水 “The Floods of Autumn”), Zhuangzi, who is crossing a bridge over the Hao river with Huizi, notes: “See how the small fish are darting about [in the water]. That is the happiness of fish.” In chapter six (Dazongshi 大宗師”Great Ancestral Master”), Zhuangzi recounts Confucius’ comments to illustrate Daoist attitudes. Confucius said: “Fish are born in water. Man is born in the Dao. If fish, born in water, seek the deep shadows of the pond or pool then they have everything they need. If man, born in the Dao, sinks deep into the shadows of non-action, forgetting aggression and worldly concern, then he has everything he needs, and his life is secure. The moral of this is that all fish need is to lose themselves in water, while all man needs is to lose himself in the Dao.” It is therefore not surprising that the depiction of fish in water came to provide a rebus for yushui hexie 魚水和拹 “may you be as harmonious as fish and water”. When the fish in the bottom of the present jade washer were covered with water they would perfectly represent this wish for harmony.

The Qianlong emperor’s great love of jade combined with his passion for antiques resulted in his commissioning significant numbers of archaistic jade items for his court, a number of which were inscribed with the characters Qianlong fanggu 乾隆仿古 – “Qianlong copying the ancient." In the case of the present jade washer, the emperor’s intentions are made quite clear from the inscription that he commanded to be applied to the base of the vessel. Of all the Ming and Qing emperors, Gaozong (the Qianlong emperor) was perhaps the most fervent collector and patron of jade carving. In the early part of his reign the emperor was frequently dissatisfied with the work of the lapidaries producing carved jades for the court and encouraged the craftsmen to achieve higher standards of perfection. One of the problems for the jade carvers in the early years of the reign was the lack of suitable jade, and it was only in the 1750s, after the punitive battles against the Dzungar tribes and Hui people, that the Xinjiang area was captured for the Chinese empire and Khotan jade was sent to the court as tribute each spring and autumn. With this newly available source of fine, raw jade, the lapidaries in the palace workshops could produce carved jade pieces of the exemplary standard sought by the emperor. Clearly, the present jade washer met the extremely high imperial expectations and was deemed a fitting vessel on which to inscribe a poem from the imperial brush and two of his imperial majesty’s favorite seals.

Rosemary Scott

Senior International Academic Consultant, Asian Art

Part II: Day Sale (Lots 1101-1422)

The Day Sale is divided into a Morning Session of Asian Works of Art (Lots 1101-1237) and an Afternoon Session for English and European Decorative Arts, Carpets, Fine Art, and Asian Works of Art (Lots 1301-1422). The morning session spans impressive bronzes, jades, Chinese and Japanese lacquerware, paintings, and Japanese gold-leaf screens. Highlights include a silver-and copper-inlaid bronze figure of a Buddha, Western Tibet, 11th-12th century ($100,000-150,000), a sandstone figure of a male deity, Khmer, Angkor period, Angkor Wat Style, 12th century ($100,000-150,000), a rare and finely carved white jade ‘Bridge Scene’ brushrest and spinach-green jade base, 18th-19th century ($80,000-120,000), and a rare carved black lacquer circular dish, Ming dynasty ($30,000-50,000).

![1102]()

![1102-1]()

![1102-2]()

![1102-3]()

Lot 1102. A silver-and copper-inlaid bronze figure of a Buddha, Western Tibet, 11th-12th century; 12 ¼ in. (31 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 150,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Seated in vajrasana upon a rectangular throne decorated with lotus petals below addorsed lions and a draped textile, the broad chest partially wrapped in a diaphanous robe with an incised diaper pattern along the hems, the face with copper-inlaid lips, downcast, silver-inlaid eyes, and arched brows, the hair covering a spherical ushnisha.

Provenance: The Pan-Asian Collection (Christian Humann, d. 1981), New York, by 1971.

Collection of Robert H. Ellsworth, New York, by 1982.

Eastern Pacific Co., Hong Kong, 9 July 1990.

The Irving Collection, no. 2944.

Literature: Marilyn Rhie and Robert A. F. Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, New York, 1991, p. 344, no. 137.

Himalayan Art Resources (himalayanart.org), item no. 31426.

Exhibited: On loan to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (L.71.29.32), by 1971.

Note: This rare bronze figure of a buddha sits in a meditative posture, his hands overlapping so that the fingertips on each of his hands reach just beyond his opposite wrist. The roundness of his downcast eyes is emphasized by the light-catching silver inlay contrasting with the copper inlay of the full lips. He is modeled with pronounced facial features, a notably short neck, round shoulders, tubular limbs, and robust proportions. The rice-grain hem of his robe, draped over the left shoulder, comes to a narrow, folded end at the shoulder in the shape of a swallow’s tail. Despite the lions adorning his square lotus throne, which typically support the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, this buddha remains iconographically unidentifiable and may represent Shakyamuni or Amitabha.

While few published examples share these stylistic details, a similar figure of a buddha, with an almost identically unusual representation of dhyanamudra, can be found in the collection of the British Museum (acc. no. 1966,0216.1). The British Museum describes the sculpture as an 8th-century Kashmiri work, whereas Ulrich von Schroeder attributes it to the sixth-century in Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, p. 112 fig. 13A. Both attributions are certainly based on the Gupta-style, full facial features and the medieval Indian-style inlay used to render the figure’s eyes and lips. The present figure certainly shares these features but is not as worn from handling, possibly suggesting a later date.

Other noticeable differences between the British Museum example and the present figure indicate a different place of origin. The distinctly Tibetan features of the present example include the details of the throne, which the Kashmiri example lacks entirely. The more-structured lotus petals and lions resemble those in early Tibetan paintings from central Tibet. As Rhie and Thurman point out in their entry for this sculpture within their 1991 publication Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, p. 344, this image is representative of the equal influence of Kashmiri and central-Tibetan styles at play in Western Tibet. The Kingdom of Ladakh, for instance, had close commercial ties with Kashmir during the period of the second dissemination known as the Tibetan Renaissance (c. 950-1200). Moreover, lions were often used indiscriminately within this early Tibetan tradition to adorn the thrones of deities, a tradition to which fourteenth-century murals at Shalu Monastery in Shigatse attest. Taking those considerations into account, the figure’s mudra makes it impossible to say whether this is the historical Buddha Shakyamuni or the tathagataAmitabha, who is typically represented with his hands in dhyanamudra. What is certain, however, is that this image was made during a critical period of artistic evolution in Tibet.

![1107]()

![1107-1]()

Lot 1107. A sandstone figure of a male deity, Khmer, Angkor period, Angkor Wat Style, 12th century; 28 in. (71.2 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 150,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Clad in a short sampot carved with parallel pleats and secured with a jeweled belt and with a double-butterfly sash in front, his rounded face with delicately outlined lips and long pendulous earlobes, the hair arranged in a cylindrical chignon and fronted by a foliate tiara, stand.

Provenance: Spink & Son, Ltd., London, 1984.

The Irving Collection, no. 933.

Note: This figure dates from the Angkor Wat period, in the twelfth century, when the Khmer Empire was at territorial zenith. This starts with the reign of Suryavarman II (r. 1113-1145), who ordered the construction of Angkor Wat, the largest temple of the Angkor period, dedicated to Vishnu. The last great king of the period, Jayavarman VII (r. 1181-1218), expanded into the territories of the Champa to the east. Jayavarman VII also adopted Mahayana Buddhism as the official state religion, replacing the cult of Vishnu which had predominated in the Khmer Empire for previous centuries.

Stylistically, the sculpture of the Angkor Wat period is marked by a return to the somewhat angular and upright modeling of the periods preceding the Baphuon style of the eleventh century. This angularity can be seen in the wide shoulders and hips of the upper torso, as well as in the drapery of the sampot, which sits roughly straight across the hips, and in the fish-tail folds which fall in heavy vertical pleats, in contrast to the earlier Baphuon period in which the drapery is full of curling flourishes. The size of sculpture from the Angkor Wat period, however, is generally in line with the more diminutive Baphuon-period works, in contrast to the monumental sculpture of the tenth century and earlier.

Many four-armed male figures from the Angkor Wat period depict the Hindu god Vishnu, unsurprisingly, given the religious beliefs of Suryavarman II. Towards the end of the twelfth century, images of Lokeshvara (Avalokiteshvara) and other Buddhist deities began to proliferate. Representations of Vishnu and Lokeshvara during this time are almost stylistically indistinguishable, save for their iconographic features. It is likely the artists of the later Angkor Wat period adopted the iconometry of Vishnu images when developing representations of Buddhist deities. See, for example, a sandstone figure of Lokeshvara from the Robert Hatfield Ellsworth Collection, sold at Christie’s, New York, 17 March 2015, lot 36. The image can only be identified by the presence of the diminutive Amitabha effigy at the front of the chignon, as the other iconographic markers which would have been held in the four arms are missing. In the present figure, there is a small triangular, shaped loss in the same place that could once have been an Amitabha image. The only remaining iconographic identifier is the object held in the proper left upper hand, although it is not entirely legible. While it could be a fragmentary representation of the conch shell, an identifier of Vishnu, the horizontal striations on either end possibly indicate it could be a sutra manuscript, which is an attribute of Lokeshvara.

![1111]()

![1111]()

![1111]()

Lot 1111. A rare and finely carved white jade ‘Bridge Scene’ brushrest and spinach-green jade base, China, Qing dynasty, 18th-19th century; 6 ½ in. (16.5 cm.) long. Estimate USD 80,000 - USD 120,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Intricately carved with a scene of figures crossing a bridge between the leafy branches of trees on the sides, with two fishermen in a sampan below, the stone of even white tone with a few minor, snowy inclusions, the river and rocky banks carved from a separate stone of spinach-green color.

Provenance: Sir Anthony Stainton (1913-1988), KCB, QC, Collection, London.

The Hartman Galleries, Inc., Palm Beach, 1986.

The Irving Collection, no. 447.

Note: This rare brush rest is testament to the skill and sensitivity displayed by the jade carvers of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Carved in the form of a miniature scene of figures crossing a bridge, but functionable as a brush rest, this piece represents a microcosm of everyday life upon which the user could meditate while going about scholarly activities. Although several comparable examples of white jade bridge-form brush rests exist within museum collections, there appear to be no published examples with spinach-green jade base representing the river. One other known example with a spinach-green base, but of somewhat larger size (8 ½ in. long overall), was sold at Christie's, Paris, 12 December 2018, lot 117. See, also, a white jade bridge-shaped brush rest in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum - 42 - Jadeware (III), Hong Kong, 1995, p. 195, no. 159. Another brush rest, of a size similar to that of the present example, also in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, is illustrated in Zhongguo yuqi quanji, vol. 6, Hebei, 1991, p. 200, no. 286.

![121934228]()

Fig. 1. A White and Spinach-Green Jade “Bridge Scene” Brush Rest, Qing dynsty, 18th – 19th century. Sold for 487,500 EUR at Christie’s Paris, 12 December 2018, lot 117. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

![1126]()

Lot 1126. A rare carved black lacquer circular dish, Ming dynasty (1368-1644); 7 ¼ in. (18.4 cm.) diam. Estimate USD 30,000 - USD 50,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

The interior well carved with two three-clawed dragons separated by the long, rippling ends of two bows "tied" either side of the narrow, raised, petal border encircling the central diaper medallion, all amidst a dense ground of leafy lotus scroll, the design repeated on the exterior with the addition of two ribbon-tied endless knots that separate the dragons.

Provenance: The Irving Collection, no. 3820

Stylistically, this rare dish may be compared to other dishes of sixteenth century date. These dishes are characterized by the density of the decoration and the style of carving that creates the impression of movement or energy. One such dish (18.1 cm. diam.), described as a typical example of Yunnan work, and at the time dated Yuan dynasty, fourteenth century, illustrated by Lee Yu-kuan in Oriental Lacquer Art, New York/Tokyo, 1972, p. 163, pl. 97, is carved with two similar dragons surrounding an endless knot amidst the scrolling stems of lotus and other water plants in a lotus pond represented by the ground of dense rolling waves. The manner in which the dragons on the Lee dish are carved, their bodies filled with diagonally set parallel ridges, can be seen on the bodies of the dragons on the present dish. This stylistic technique is also seen on the bodies of three lions and a dragon encircling a ribbon-tied brocade ball in the center of a carved red lacquer dish (17 cm. diam.), described as Yunnan style, from the Lee Family Collection, Part II, sold at Christie's, Hong Kong, 28 November 2012, lot 2105. On this dish the brocade ball is tied with four bows, the trailing ends of the ribbons rippling around and between the four animals racing amidst a dense field of scrolls, coins and chimes. The same carving technique can be seen on the bodies of four lions on a brown and red lacquer dish (16.9 cm. diam.) dated early sixteenth century, in the Linden-Museum, Stuttgart, illustrated by Monika Kopplin, Im Zeichen des Drachen, Museum für Lackkunst, Munster, 2006, pp. 132-33, pl. 52. On this dish the lions are separated and surrounded by the knotted and trailing ends of four ribbons "tied" to the sides of a raised diaper border encircling a medallion of a kneeling foreigner on a gold ground. A black lacquer rectangular tray, dated fifteenth-sixteenth century, from the collection of Jean-Pierre Dubosc, illustrated in Chinese lacquer from the Jean-Pierre Dubosc collection and others, Eskenazi, London, December 1992, pl. 17, displays two similarly carved lions flanking a ribbon-tied brocade ball in a similarly dense field of decoration. The catalogue entry notes that "this type of lacquer is generally known as Yunnan ware."

Lacquer dishes with a central diaper medallion can first be seen in the Song dynasty. A black and red lacquer dish (18.8 cm. diam.), dated to the Song dynasty, illustrated in The Colors and Forms of Song and Yuan China, Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, Tokyo, 2004, pl. 112, has a diaper medallion within a diaper border set between two raised rings. The outer field of the Nezu Institute dish is decorated with peony scroll.

The afternoon session presents a selection of decorative arts from the Irvings’ New York City apartment. Included in the offering English and European decorative arts, carpets, fine art, Asian works of art, and a group of art reference books. Among the featured lots are a set of eight George III solid mahogany dining chairs, possibly by Wright & Elwick, circa 1765 ($40,000-60,000); a Chinese Export reverse mirror painting, last quarter 18th century ($25,000-40,000); and a pair of George III silver candelabra by John Wakelin & William Taylor, 1777 ($20,000-30,000).

![1315]()

![1315]()

Lot 1315. A set of eight George III solid mahogany dining chairs, possibly by Wright & Elwick, circa 1765. Estimate USD 40,000 - USD 60,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Each with pierced back above a yellow silk damask covered seat on shell and acanthus carved legs terminating in scrolled feet, minor variations to carving; together with four George III style mahogany dining chairs, modern.

Provenance: Acquired from Partridge, London.

The Irving Collection, no. DR01.

Literature: F.L. Hinckley, A Directory of Queen Anne, Early Georgian and Chippendale Furniture, New York, 1971, pl. 125, fig. 263.

Eight chairs from this set were illustrated in the Partridge Summer Exhibition Yearbook, 1990, no. 22.

Note: Eight chairs from this set were illustrated in the Partridge Summer Exhibition Yearbook, 1990, no. 22. These chairs are closely related to a set of twelve chairs at Nostell Priory, Yorkshire, which were possibly supplied by Wright & Elwick of Wakefield, and probably those recorded in the household inventories of 1806 and 1812 as '12 Mahog- Chairs and Castors'. The attribution to Wright & Elwick is based on a further set of closely related chairs thought to have been supplied by the firm to Kippax Park, Yorkshire (see Moss Harris, The English Chair, London, 1946, p. 123). Wright & Elwick were undoubtedly employed at Nostell; in a letter to Sir Rowland Winn dated 26 August 1767, Chippendale was obliged to confess why he had failed to dye some old crimson wall hangings: ‘I find it will not take a garter blue as the Ingenious Mr. Elwick said it would, I trusted his knowledge for which I am sorely vexd, it will take a dark blue and no other coloure’ (L. Boynton, N. Goodison, ‘Thomas Chippendale at Nostell Priory’, Furniture History, 1968, p. 22).

![1346]()

Lot 1346. A Chinese Export reverse mirror painting, China, Qing dynasty, last quarter 18th century, 40 in. (101.5 cm.) high, 31 ¼ in. (79.5 cm.) wide. Estimate USD 25,000 - USD 40,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Depicting figures in a pagoda by a river with deer in the foreground, within a George II style giltwood frame.

Provenance: Acquired from The Oriental Art Gallery Ltd., London, 20 October 1993.

The Irving Collection, no. BR17.

Lot 1320. A pair of George III silver candelabra by John Wakelin & William Taylor, 1777 Estimate USD 20,000 - USD 30,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Online Sale (Lots 1-68)

The online sale, Contemporary Clay: Yixing Pottery from the Irving Collection, takes place from March 19-26 and comprises 68 teapots, figures and objects made by well-known Yixing pottery artists. Florence and Herbert Irving, known for their great eye for exceptional quality in art and form, appreciated the unique charm of contemporary Yixing ware. Steeped in earlier Ming and Qing traditions, while drawing creative inspiration from nature and the daily life, each potter has a distinct style.