fig. 5. Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18.

The poem and the Qianlong Emperor’s annotation to it indicate that the bowl was sent as a tribute from the ruler of the Hui. According to the research of Deng Shuping, the bowl came from the Yarkent Khanate in southern Xinjiang as a tribute through emissaries from Labunidun, ruler of the Altishahrs. Labunidun’s sister became a consort of the Qianlong Emperor and the Fragrant Concubine of popular lore. This jade bowl may very well have travelled to Beijing together with the Fragrant Concubine.6

High-footed and thick-walled jade bowls were popular in Central Asia between the 15th and the 18th centuries. They were primarily used to serve milk tea by nomads of the eastern plains of Central Asia, and were important personal objects. For these nomads, to give one’s own jade bowl to another person was to show the highest respect. Unfortunately, not all Chinese emperors understood this. According to Ming Taizong shilu [Veritable records of the Yongle reign], in 1406 the Yongle Emperor received a jade bowl as a tribute from the Altishahr emissary Huihuijieyasi, but had it sent back, citing as a reason that “the Chinese porcelain used in our court is pure and lustrous. It suits our heart. We do not need this…”7

The Yongle Emperor rejected the tribute for several reasons. First, he had little interest in jade, preferring the purity of porcelain. Second, in the sedentary culture of the Han Chinese, a bowl was an everyday vessel; the Yongle Emperor did not understand the jade bowl’s significance in nomadic cultures and failed to see it as valuable. Given the popularity of high-footed and thick-walled jade bowls during this period, the Yongle Emperor very likely received one of them. Due to his refusal, we have been deprived of a specimen of 15th-century Central Asian jade bowls.

Among Chinese emperors, the Qianlong Emperor best understood the jade bowl’s importance to the nomadic peoples of the Steppes. He was personally fond of jade, but more significant was the Manchus’ origin as nomadic hunter-gathers in the northwest. No stranger to life on horseback, the Qianlong Emperor appreciated the meaning of the jade bowls sent to him as tributes from Central Asia and reciprocated with even more valuable gifts, as he wrote humorously in his poem on the 1758 bowl (fig. 6).8

![Inscribed green jade bowl, yuyong mark and period of Qianlong Qing court collection. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing]()

fig. 6. Inscribed green jade bowl, yuyong mark and period of Qianlong Qing court collection. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

However, because the first three jade bowls that the Qianlong Emperor received were crafted from green jade of ordinary quality, he did not use them in his tea-bestowal ceremonies. Only in the 30th year of his reign, when he received the white jade bowl of high quality from Central Asia, did he have it inscribed with his own poem, decorated with decorative patterns, and used as a ceremonial vessel. It is as yet impossible to determine whether this jade bowl is the one in Taipei. However, the current lot was definitely a bowl created on the Qianlong Emperor’s order from Khotan white jade for tea-bestowal ceremonies. The Qianlong Emperor’s poems on these three bowls are the earliest extant poems known to me by the Emperor on jade bowls meant for these ceremonies. In other words, these three bowls are the earliest bowls definitely used for these ceremonies.

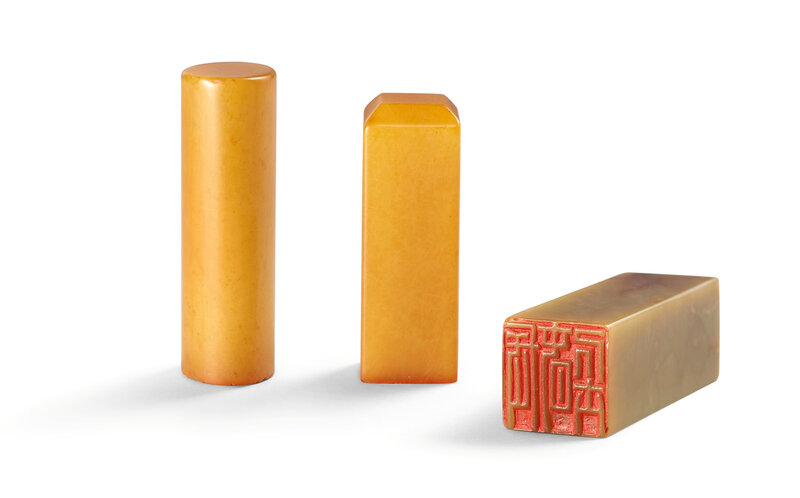

Let us now consider the difference between the reign marks ‘Qianlong yuyong’ and ‘Qianlong nianzhi’. In my survey of jades formerly in the Qing imperial court, I have found that objects bearing the former reign mark are far fewer than those bearing the latter, and the two groups also differ in object types. ‘Qianlong yuyong’ is inscribed primarily on two types of objects. The first is tributary jades from elsewhere and jades remaining from previous dynasties, as suggested by an entry from the 44th year of the Qianlong reign in palace workshop records on a tributary ‘Huizi’ bowl to be carved with the reign mark ‘Qianlong yuyong’.9

As mentioned above, the jade bowl that the Qianlong Emperor received from Xinjiang in 1758 is carved in relief with the reign mark ‘Qianlong yuyong’. Other Hindustan jades from the Qing imperial collection also bear this mark, as do jades from previous dynasties, such as the Ming, that remained in the Qing court collection.

The second type of jades bearing the reign mark ‘Qianlong yuyong’ are newly created ones that the Qianlong Emperor personally treasured, such as two white bowls recorded in entries from the 45th year of the Qianlong reign. These were respectively made by Ruyiguan craftsmen from sketches by the court painter Yang Dazhang and inscribed with poems by Zhu Yongtai. On the Qianlong Emperor’s personal order, both were carved with the reign mark ‘Qianlong yuyong’.10

In short, the reign mark ‘Qianlong yuyong’ expressed the Emperor’s personal preference and denoted vessels reserved for his personal use, regardless of place and time of creation.

The reign mark ‘Qianlong nianzhi’ is most commonly found on Qianlong-period jades. It primarily denotes newly created jade objects of high quality used and collected by the court, although it is found also on a very limited number of historical jade objects refashioned by the Qianlong court. The reign mark is mentioned very frequently in the records of the Qing court workshop.11

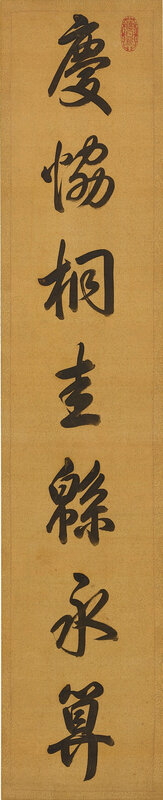

Qing court records indicate that reign marks carved on Qianlong-period jades, whether in clerical, seal, or regular script, were based on brush-written designs by calligraphers. Sometimes the designs were attached to the jades for the Emperor’s approval before execution. The Qianlong Emperor cared a great deal about his own poetic compositions. These were sometimes rendered in calligraphy by the Emperor himself, and sometimes by high ministers and professional calligraphers. The calligraphic models were then transferred to the jades by specially trained carvers. The process is fundamentally similar to the traditional process of reproducing calligraphy in stone stelae. These inscriptions in jades retained the calligrapher’s manner and intent, and for this reason the calligraphy found on Qianlong-period jades is of a quality unsurpassed by inscribed jades from other periods. Known jade inscribers in the Qianlong court include Zhu Yongtai, Zhu Shiyun, and Zhu Cai.

Aside from the Qianlong Emperor’s appreciation of the importance of jade bowls in nomadic culture and the Manchus’ own tea-drinking customs, the Emperor also had a more profound and personal reason for his love of jade bowls. In 1775 and 1786 respectively, he wrote poems in praise of a jade bowl (fig. 7) and a Khotan white jade bowl (fig. 8). In his annotations to them, he indicated that the tea-bestowal ceremonies were a symbolic expression of his benevolence towards his subjects. These poems are inscribed on four jade bowls in the Palace Museum collection (figs 9 and 10),13 which were used in tea-bestowal ceremonies like the aforementioned three bowls. Jade bowls reminded the Qianlong Emperor of a quotation attributed to Confucius in Hanfeizi: “The ruler is like the yu vessel, and the people like water. If the yu is square, the water is square. If the yu is round, the water is round.”14 Substituting the bowl for the yu vessel, the Qianlong Emperor took it as a symbol of his benevolent and just rule, which would ensure the continual peace and prosperity of his realm.

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18]()

fig. 7. Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18

fig. 8. Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi wu ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 5], juan 23, p. 8

fig. 9. Inscribed green jade bowl, yuyong seal mark and period of Qianlong Qing court collection. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

![Gold-inlaid and embellished white jade bowl, mark and period of Qianlong. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing]()

fig. 10. Gold-inlaid and embellished white jade bowl, mark and period of Qianlong. Image Courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing.

Among the jade bowls definitely used for the Qianlong Emperor’s tea-bestowal ceremonies, there is only one made from green jade; all of the other six were made from white jade that satisfies the aesthetic requirement of resembling mutton fat. The Qianlong Emperor expressed his preferences clearly in a poem: “Among the five colours, white should naturally come first; bowls with the appropriate circumstance and capacity are the finest”.15 The dimensions of the extant jade bowls conform to the standards of the Qing court.16

As a sign of his passion for jade bowls, the Qianlong Emperor wrote around 30 poems on them throughout his life. These were inscribed on jade bowls from different periods. Moreover, under his reign, a staggering amount of jade bowls were made, surpassing the quantities of all other types of jade. Jade bowls in the Palace Museum collection alone number over 2000.

To be sure, most of these jade bowls were ordinary utensils meant for banquets. They were often made from large pieces of raw jade or from material hollowed from larger vessels, including shanliao jade. These bowls were often made in dining sets alongside basins, plates, and cups to ensure consistency of colour, although they far outnumbered other vessels. An entry from the 44th year of the Qianlong reign in the palace workshop records, for example, refers to the creation of 42 jade bowls and 12 jade plates.17

Extant documentation indicates that banquets during the later part of the Qianlong reign required vast quantities of jade bowls, each necessitating the creation of over a hundred of them. Such large-scale production was only possible because of improved efficiency enabled by innovations in tools and techniques. The lathe was invented during this period, and most of the tea bowls in the Qianlong court were created on lathes. The palace workshops recorded hiring “lathe experts” like Pingqi and Zhu Yunzhang to teach younger jade craftsmen how to operate lathes.18

The most important component in a lathe was the bowl-shaped grinding wheel (wantuo), which enabled the efficient creation of thin-walled bowls of uniform shapes and dimensions.

Although jade bowls are relatively simple in form, they still required the Qianlong Emperor’s approval. On the third month of the 25th year of the Qianlong reign, the Zaobanchu created a wood model of a jade bowl for the Qianlong Emperor’s inspection. The Emperor approved the design and ordered a jade bowl created according to it. Such wood models were also sent to the Suzhou manufactory and other workshops for reproduction.

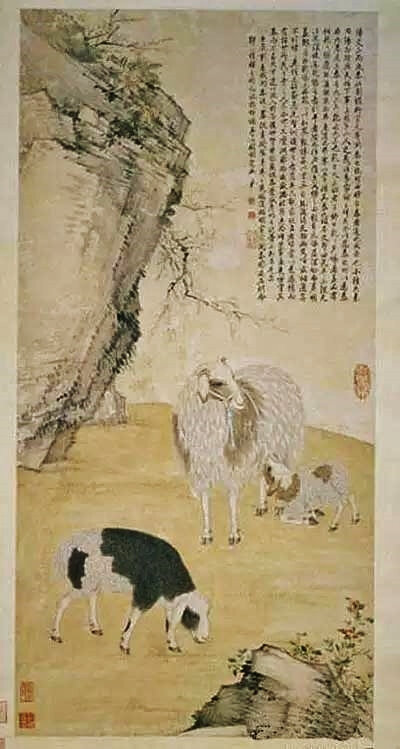

Because most jade bowls were undecorated, they required raw jade of high quality. Jades with noticeable cracks or blemishes could not be used. As a result, despite the vast amount of jade bowls created by the Qing court, few were of a quality suitable for display or ceremonial use. Those that were mostly created from high-quality white jade, usually Khotan jade but occasionally shanliao jade also. Because Qing-period shanliao jade tended towards green, Khotan white jade was more usually used. The famous white jade sculpture Lady under Wutong Trees was in fact made from the remnant of a piece of raw Khotan white jade used to make bowls. It typifies the warm, mutton-fat white colour that Qianlong preferred.

Carved from Khotan white jade, the jade bowl presently on offer at Sotheby’s has a warm tonality and pure and “fatty” lustre. The textual inscription around its body and the reign mark beneath it showcase the masterful craftsmanship of the jade inscribers of the Qing court. As one of the earliest bowls used by the Qianlong Emperor’s in his tea-bestowal ceremonies, it is a rare treasure of Qing court art.

1 Qing Gaozong (Qianlong) yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Beijing, 1993, Yuzhi shi san ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 3], juan 53, p. 2.

2 Yang Shen, Danqian zonglu, vol. 3.

3 Empty Vessels, Replenished Minds. The Culture, Practice and Art of Tea, Taipei, 2002, cat. no. 165.

4 Zhang Guangwen, ed., The Complete Collection of Treasures in the Palace Museum. Jadeware (III), Shanghai, 2008, no. 223.

5 See note 1, Yuzhi shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18.

6 Deng Shuping, ed., Exquisite Beauty – Islamic Jades, Taipei, 2007, pp. 28-30. Deng Shuping, ‘Xiangfei de yuwan’, Bulletin of the National Palace Museum, 1983, vol. 1, issue 1, pp. 88-92.

7 Ming Taizu shilu [Veritable records of Emperor Taizong of the Ming dynasty]. Here the jade bowl is mistakenly recorded as a jade pillow, but the section on Chengzu in the Mingshi [Historian of the Ming dynasty].

8 See note 4, no. 220.

9 First Historical Archives of China and Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, eds, Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu huoji dang’an zonghui [Documents in the Archives of the Workshop of the Qing Palace Imperial Household Department], Beijing, 2005, vol. 42, Ruyiguan, p. 716.

10 Ibid., vol. 44, Ruyiguan, pp. 38-39.

11 Ibid., vol. 42, Ruyiguan, pp. 708-709; vol. 44, Ruyiguan, p. 48.

12 See note 1, Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18; Yuzhi shi wu ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 5], juan 23, p. 8.

13 See note 4, no. 217.

14 ‘Waichushuozuoshang’, Hanfeizi, passage 32.

15 See note 1, juan 98, p. 34.

16 On the standard dimensions of bowls used in the Qing court, see Liao Baoxiu, ‘Cong sede huafalang yu yangcai ciqi tan wenwu dingming wenti [On naming artefacts: a study based on colour-ground enamelled wares and yangcai porcelains]’, The National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art, issue 321, December 2009.

17 See note 9, vol. 30, xingwen [general text], p. 772.

18 Ibid., vol. 42, Records of the imperial workshops dated to the 44th year of the Qianlong period, p. 666.

![1]()

![2]()

![3]()

![4]()

Lot 3204. An extremely rare large imperial white and russet jade 'calendar' plaque, Yuzhi mark and period of Qianlong (1736-1795); 19.5 cm, 7 5/8 in. Estimate: 2,000,000-3,000,000 HKD. Lot sold 3,240,000 HKD (413,294 USD). Courtesy Sotheby's.

the oval plaque skilfully worked with a central elongated aperture enclosing Yuncai tongzi (Boy of wealth), the figure rendered in openwork and depicted holding a circular ring and a gold nugget, the front side of the plaque decorated in low relief with the Ten Heavenly Stems in seal script encircling the aperture, the reverse incised with the Twelve Earthly Branches in regular script, all surmounted by a crouching demon figure, possibly a garuda, amidst scrolling clouds, above a ferocious scaly dragon emerging from swirling clouds at the base, the sides inscribed with a Qianlong yuzhi mark and an inscription reading Jiazi wannian ('Ten thousand years of the jiazi cyclical year'), the smoothly polished stone of an even white colour with warm russet patches and veining.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 26th October 2003, lot 39.

Note: This exceptionally rare plaque, of an impressive size measuring almost 20 cm in length, subtly illustrates the Qianlong Emperor’s position as the ‘Son of Heaven’. The Chinese rulers believed they ruled by heavenly mandate and every element of the present piece serves symbolically to affirm Qianlong as Emperor, from references to the lunar system to the dragon at the bottom. In style it is reminiscent of Han dynasty bi discs and its archaistic flavour, achieved in its colour, shape and carving style, is not only in accordance with the Emperor’s taste but also serves to further legitimise his throne. The importance of this piece is indicated by the Qianlong yuzhi ('made to imperial order') mark on the side. No other related example appears to have been published, although according to the Archive of the Qing Imperial Workshop, a white jade wannian jiazi plaque was sent to the court in the 45th year of the Qianlong reign (in accordance with 1780).

Carved in low relief on one side are the Ten Heavenly Stems and incised on the other are the Twelve Earthly Branches (tiangan dizhi). Together these two sets create the Chinese system that is used to count the years, months and days, as well as the two-hour periods (shi) which divides the twenty-four-hour day into twelve periods. In this lunar calendar, each year is assigned one of the Twelve Earthly Branches and an animal from the Chinese zodiac. Each unit in a cycle, whether it represents a year or minute, is assigned one stem and one branch. The Ten Stems and Twelve Branches run concurrently so a whole cycle takes sixty years to complete and for the Stems and Branches to once again coincide. Notably, this full cycle is also known as jiazi, as inscribed on one side of the plaque.

The direct representation of the Chinese lunar calendar in jade is also found on two sets of white jade zodiac figures, one held in the Palace Museum, Beijing, and the other in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. The twelve anthropomorphic figures were stored inside a box known as wannian jiazi he and arranged around a central rectangular jade box carved with the Daoist qian trigram, a symbol of the Qianlong Emperor. According to the Archive of the Imperial workshop, a complete set was made by imperial commission on the 21st day of the 5th month of the 48th year of Qianlong reign (in accordance with 1783), which was placed in Maoqindian (Hall of Merit and Diligence).

Akin to the zodiac figure sets, the present plaque appears to portray the Qianlong Emperor as the Son of Heaven; uniformly established and protected by celestial guardians to bring prosperity to the empire, as suggested by the central figure of Yuncai tongzi. This theme of establishment and protection is further suggested by the demon-like figure at the top of the plaque which may be a garuda, a guardian figure in Tibetan Buddhism. The dragon emerging from waves on the base draws attention to the imperial nature of this piece.

A much smaller white jade plaque, similarly carved with the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches surrounding Yuncai tongzi in the centre, attributed to the Qing dynasty, was sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 6th October 2012, lot 18, from the Yidetang collection.

Sotheby's. Qianlong – Scholar and Calligrapher, Hong Kong, 03 Oct 2018

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi san ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 3], juan 52, p. 2](http://i.pinimg.com/564x/33/9b/2c/339b2c8be007ad15daa08eddeeb73e19.jpg)

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18](http://i.pinimg.com/564x/a3/ce/bf/a3cebfa24d2a98be2afaff1f6a4bab76.jpg)

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18](http://i.pinimg.com/564x/35/6a/6b/356a6bc25cbbd3ad5237e8341ca34c57.jpg)

![Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi shi wu ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 5], juan 23, p. 8](http://i.pinimg.com/564x/32/96/a0/3296a081cdac364825f960d116ab7fd5.jpg)